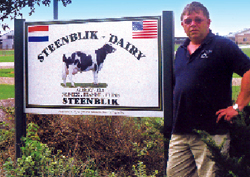

Michigan dairyman Albert Steenblik

is staying ahead of the manure management regulatory curve with the

help of a package of record keeping services from a local firm, Harvey

Milling Co.

Manure water—from the flush system—is moved from two pits and is used for irrigation on the Steenblik farm operation. Manure water—from the flush system—is moved from two pits and is used for irrigation on the Steenblik farm operation. |

Michigan dairyman Albert Steenblik is staying ahead of the manure management regulatory curve with the help of a package of record keeping services from a local firm, Harvey Milling Co.

When it comes to manure management, Michigan dairyman Albert Steenblik believes in keeping it simple.

Steenblik has expanded his dairy operation several times since first setting it up in 1994, after emigrating to the United States from Holland. He started with 250 cows in 1994, added a new barn and additional cows in 1998, and a new parlor in 2001. The latest expansion sees the dairy going to 1,800 cows with a new barn.

Albert Steenblik Albert Steenblik |

The manure is generally applied a couple of times, in the summer and in the fall. “We knife it in six or eight inches,” Steenblik explains. “It saves the nitrogen and that way nothing goes up in the air. The value we get out of knifing it into the ground is amazing. Our nitrogen bill is a fraction—probably 20 percent—of what it used to be. ”

While he notes there is a lot of talk in the industry about digesters and other technologies, he’s going to stick with the tried and true: storage pits and field application.

“I’m not saying that what we are doing is the be-all and end-all in handling manure,” he says. “I’d be happy if someone came up with a better, and more economical, way to manage manure tomorrow. I’d be first in line to adopt it. But I just don’t feel it’s out there right now.”

He added that there are a lot of different methods and technologies being tried out—but so far, no “silver bullet” or clearly superior approach has emerged.

The process at Steenblik Dairy is straightforward right now. Manure goes to the farm’s 13 million-gallon pit. A two million-gallon pit and a new 10 million-gallon pit handle water storage from the flush system in the parlor, with the water used for irrigation. “From the pit, we haul four to five weeks in the spring, three weeks in the summer and then four to five weeks in the fall, and then we’re done. We don’t have to worry about it for the rest of the year.”

Some of the approaches being promoted for manure management, while they have some benefits, can complicate the manure management process, he feels. And, he adds, they can carry some pretty hefty price tags.

That said, Steenblik remains open to exploring other manure management methods. “The worst thing would be to stick your head in the sand and think you know everything. We don’t want to be doing that.” He’s carefully watching what others are doing out there in manure management. Being open to incorporating new ideas on the dairy, in all of its operations, from cow care to manure management is important, he feels.

Using Houle pumps and Houle tanks, as well as three semi-tankers, the Steenblik Dairy does its own manure application. “It’s a lot of work, but we’re big enough to afford to have our own equipment.” Having their own equipment also gives them a great deal of flexibility with regards to application. That might not be available if they went the custom applicator route. “We farm all our own ground, so we have control over when and where we can apply the manure.”

Albert Steenblik notes that they work to get maximum use of the manure from their 1,800-cow dairy on their land, knifing it in six or eight inches. “The value we get out of knifing it into the ground is amazing. Our nitrogen bill is a fraction of what it used to be.” Albert Steenblik notes that they work to get maximum use of the manure from their 1,800-cow dairy on their land, knifing it in six or eight inches. “The value we get out of knifing it into the ground is amazing. Our nitrogen bill is a fraction of what it used to be.” |

While the Steenblik Dairy handles most of the manure management related work, one thing Albert is happy to contract out is the overall record keeping. Over the past year, he’s used the Harvey’s Farm Cycle package of services, including manure management, and it’s worked out well.

Like a lot of large dairy operators, Steenblik has come to the prudent realization that he—and his farm employees—can’t do it all. And with manure, the record keeping is a task that can be easily contracted out.

“I run the cash crop side of the operations, and we have good people who take care of the cows. Once we do all that, there’s not a whole lot of time left to do other things.”

Jim Sheppard, who heads up the Farm Cycle service operated by Harvey Milling Company Co, of Carson City, Michigan, notes that livestock operators, especially large scale operations, are facing daily challenges with their farm operations. “One of these challenges is the continued protection of the environment from nutrient build-up from manure application,” he says. “Proper record keeping is really essential for monitoring soil nutrient levels and maximizing the value of manure as a resource.”

The Farm Cycle program provides an easy format to track and document manure applications, pesticide use, fertilizer use, and the crop yields necessary for a farm’s Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan, Michigan’s Agriculture Environmental Assurance Program (MAEP) and Generally Accepted Agricultural and Management Practices (GAAMP).

With the program, the farm documents all manure—as well as fertilizer and pesticide—applications, and then reviews the information with Sheppard in an interview, usually lasting about an hour. Using a computer database system, Harvey Milling tracks manure application on a field-by-field basis and whole farm balances of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium—essentially keeping all the farm’s nutrient records up to date.

Sheppard notes that the program was developed by his predecessor, Chuck Frendt.

“Chuck felt there was a real need out there to help farms track their nutrients,” he says. In developing the program, Frendt worked with dairy operations, asking them what they needed in terms of information, and talked to a number of suppliers, like ADM, about what else could be included, like feed values.

“Chuck came up with this really neat program that tracks everything that goes on the farm and everything that comes off the farm.

“What we’ve done from there is teamed up with Harvey’s agronomy division, which does soil testing, and incorporated that into our reports, so the dairy can look at their base levels of phosphorus and potassium. Then we take the actual manure tests results, the rates applied per acre, and we can tell the dairy how much phosphorus and nitrogen needs to go on the fields to make the best use of nutrients.”

Sheppard notes that similar programs could be set up with a good database spreadsheet program. “The unique thing with the Farm Cycle program is that we’ve got agronomists on staff that are looking at these reports and trying to catch an area of concern before we have an issue. If they see an elevated phosphorus level, we’re alerting the farm ahead of time about it. It’s another set of eyes looking at their operations and helping make sure things stay on track.”

The agronomists are also looking at the big picture for each of the farms. They continually review nutrient levels, how much manure is being applied and can better structure their crop recommendations for the farms.

The reports are also helpful when it comes to the Comprehensive Manure Nutrient Management Plans, which must be reviewed each year.

The program is also flexible in what it can cover off. For example, the agronomists were tracking how many pounds of manure are applied per acre for one dairy. “But the dairy operator had people asking him how much manure he was putting on there, and he wanted to know how many gallons per acre,” says Sheppard. “So we included that in the program.”

The farm interviews to gather information are done once a month. Sheppard initially thought this might be too often, and offered dairies the option of perhaps doing the interviews every two months. “But they were unanimous in saying, ‘No, we need to do it once a month. If we don’t do it once a month, we’ll lose track of where we are and not be up to date.’

“And they are all very adamant about being up to date on their records.”

During each interview, Sheppard reviews the printed report that is generated from the information provided from the previous interview, covering a 30-day period.

A report, depending on the size of the farm, can range from 50 to 100 pages in length. Most of the dairies want the reports in printed form, although they are also available on CD. One dairy operator in particular was very firm about wanting the reports in hard copy. “He told me that ‘if someone walks in the door tomorrow, I know where I can get the report and give them every bit of information they might be looking for’,” says Sheppard. And those records are detailed.

Complaints—whether they are valid or not—are lodged against dairy operations from time to time, and the Steenblik Dairy is no different in this regard. “The Department of Environmental Quality came in to investigate, and Albert had all the records to give to them—it satisfied all the concerns they had. The DEQ came away very happy with the records he was keeping and how he was managing his business.

“It worked out real well,” adds Sheppard, who says he wasn’t surprised, considering all the work that goes into the reports. “If you have a professional, complete report with the details on everything you’ve done, there’s quite a bit more comfort with that than handing the DEQ a shoebox full of papers with your manure application records.”

Staff at Harvey Milling regularly review the programs, to see what can be added. For example, some pesticide information was required under Michigan’s Right to Farm Act, which provides farmers with protection from nuisance lawsuits. That was recently—and easily—added in to the program.

And through their contacts with the DEQ, they get a head’s up on what might be coming down the pipe, in terms of new regulations. “We’ve got an outline of things that have not been approved yet, but probably will be in the next year or two. We’ve gone ahead and incorporated these into the program, as well.”

The Steenblik dairy operation employs three semi-tankers, as well as using Houle pumps and Houle tanks, as part of its manure management equipment line-up. The Steenblik dairy operation employs three semi-tankers, as well as using Houle pumps and Houle tanks, as part of its manure management equipment line-up. |

And their dairy farm customers very much support this pro-active approach. “Once you explain that they don’t have to do it now, but that they might need to do it a year or two down the road, they get on side. It puts them in a good position in that they are ahead of things.”

Being ahead of the curve can be very helpful when it comes to dealing with regulatory officials. “There’s nothing that impresses an enforcement person more than when they come out to a farm and find out that you are already doing something that is not required. It gives them more assurance that you are trying to do what is right.” If worse comes to worse, and a regulatory agency decides to do an audit of a farm, the farm is prepared, with a full set of records.

The dairies that are participating in the program are customers of Harvey Milling in other areas—buying feed, seed or having them do commercial fertilizing for them. So there was already a business relationship in place.

“We were looking at it with the idea of what are these operations going to need,” says Sheppard. “The Farm Cycle program just made sense because we were touching their businesses in so many different areas already that we felt we could work with them to help us develop the program.”

The dairies were guinea pigs, in effect, but very willing guinea pigs. “They’ve been great about it. They are very vocal—if they need something different or feel something is not of value to them, they let us know.”

Harvey Milling staff have also been told—by the different farm agencies— that the reports are helpful when a farm is part of a federal or state ag program. These programs often need documentation, and it’s usually already there in the reports, making it easier to comply or qualify for these programs.

And the raw—so to speak—material for all these reports? Sheppard jokes that it comes in a variety of forms. One farm keeps a book in the tractor for record keeping and it’s covered in manure. “Essentially, we take all those load sheets, some that are just covered with manure, input the information and put together a nice clean computer report.”

Presently, the dairies working with the program are all large, but this was by design. Harvey Milling went to the bigger dairies because they knew they would offer a diversity of issues and more issues than smaller farms. “We’ve had a lot more things to deal with on the big dairies and that means we’ve ended up with a more comprehensive program in the end. But the way the program is set up, it would work just as well for a 50-head operation as a 5,000-head operation.”

And the costs for the program are reasonable. There is a charge of $300 a month, but that is reduced if the dairy does other business with Harvey Milling. They will do the set-up for free, and offer three months of free reports.

“Three months gives us the chance to make sure we sure we’ve got everything they need in the program because there is a fair bit involved in setting it up,” explains Sheppard. “Their dairy might not see the benefit in the first two months. But by the third month, we should have everything they need in place and be up to date, and they should start seeing the immediate benefit of tracking what they are doing.

“Our whole goal” Sheppard summarizes, “is to help the dairy operators manage their nutrients in the most environmental and economical way. We want to help them maximize the use of manure as a nutrient, and have it as an asset, not a liability.”