Hord Livestock Co. Inc. strives to

make their 11,000 sow farm an asset to the community, with a sound

manure management plan, and ways to communicate – through a

neighborhood newsletter and its own website – what’s going on at the

farm.

Hord Livestock Co. Inc. strives to make their 11,000 sow farm an asset to the community, with a sound manure management plan, and ways to communicate – through a neighborhood newsletter and its own website – what’s going on at the farm.

|

Pat Hord sometimes calls himself an environmental activist. This may seem strange, coming from the man who runs Hord Livestock Co., a family-owned swine operation in Bucyrus, Ohio, consisting of 11,000 sows, 4,500 acres of corn, soybean and wheat, as well as a feed mill.

But Hord is not one of those “picket sign-waver” types you might see at a protest. Instead, he feels strongly that being an environmental activist is about doing your part every day.

Pat Hord: Making good day-to-day decisions Pat Hord: Making good day-to-day decisions about the environment. |

“I like to call myself an environmental activist because it creates a mental picture. Sometimes people jump on causes just for the cause’s sake. But we’re trying to make improvements by actually being out here actively doing it every day, instead of being part of a media or political agenda. I think it’s something that all of us should be doing – getting the word out about how we as farmers are striving to make good day-to-day decisions about the environment and care of our animals.”

Hord Livestock and its 80-plus employees walk the talk. They are dedicated to managing the land and livestock by using all the environmentally sound practices available to them – from precise methods for manure application to being part of the Environmental Assurance Program. And that willingness to go the extra mile garnered them the Pork Checkoff 2006 Pork Industry Environmental Steward award.

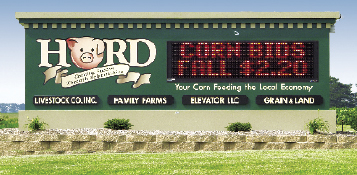

“It all starts with a firm belief that we are stewards of the land,” says Hord. “On some of our printed materials and on a sign out in front of the farm, we state that we care for the land and the animals that are entrusted to our care. It’s an important part of what we do.” And it’s what they’ve been doing for decades as they’ve passed the land down through generations.

Pat’s grandfather established the farm in 1947 with 140 acres of rented land and 10 gilts. His son, Duane, took it to the next level beginning in the 1960s, by adding sow barns, and growing the crop enterprise to 2,800-acres. In 1987 Duane’s son, Pat, came on board and during the 1990s the farm went through another expansion to remain competitive.

|

One of the ways Hord Livestock strives to be environmentally sensitive is through effective manure management. The farm today is comprised of four locations – Chapel Hill, Pine View, Killdeer Plains and Temple Woods. Each is approximately the same size and at each location land application of manure is handled similarly.

The Temple Woods Farm, for example, has 2,400 sows and two barns – one 80 feet x 600 feet and the other 80 feet x 300 feet. The manure is stored under the gestation portion (80 feet x 600 feet) in a 10-foot-deep pit that holds between 2.5 and 2.8 million gallons.

“We have nine months of storage,” says Hord. “We typically apply manure every summer on the wheat crop. We may come back in the fall and empty it out. And occasionally, we apply manure in the spring, depending on the weather.”

Before any manure is applied, soil samples are taken and the manure is tested to make sure the application falls within the recommendations of the Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan (CNMP).

“We also have an agronomy consultant that helps us balance the manure and commercial fertilizer,” says Hord. “We want to utilize the manure, but if it isn’t supplying us with the nutrients we need, we make up for that with commercial fertilizer.”

When it comes time to apply, Hord Livestock uses a six-inch dragline system. The manure is pumped through the line and applied to the fields with either an Aerway or Gen-Til system. “A spike shatters the soil structure in that top six- or eight-inches of the soil, and makes the soil act like a sponge and ready to accept the manure,” explains Hord. “It keeps the nutrients in what our agronomist calls the ‘feeder root zone.’ ”

For the Temple Woods location, the CNMP calls for the manure to be applied on approximately 800 acres. All of the locations, except for Temple Woods, have enough acres to spread on. At the Temple Woods location, relationships with adjacent farms have been developed so they are able to spread on their fields as well.

And although Hord says they have considered selling the manure, they haven’t pursued it. “Some of the manure, especially the sow farm manure, has a lower nutrient value than the finishing manure. So although it has value, we have continued to spread versus trying to sell a product.”

To ensure application is done correctly and the rates are precise, the Hord team uses a GPS system. “We test the soil every three years to know exactly what’s happening and if we’re building nutrients. That process is where we use GPS grid sampling,” explains Hord. “We take the soil samples from a grid, created on the computer. Then a receiver is mounted to a four-wheeler and we’re able to drive to the exact point we took samples the last time. We avoid random testing and we can make good decisions about application rates.”

Controlling odor is also a concern, especially with a farm the size of Hord’s. The Temple Woods location is unique. As the name suggests, it’s nestled close to a woods and there are trees on two sides. “We feel like we get good odor control by just being next to the woods. It seems to filter it out some,” says Hord. “The other advantage is that we have a quarry on the east side so there’s no housing close by.”

At the other locations, where they don’t have such an advantageous location for odor control, rows of trees have been planted as wind breaks to dissipate the odor, and add to the aesthetics.

“We continue to plant trees and think they are a good practice,” says Hord. “Depending on where we are planting them, we may grow a row of fast-growing poplar trees that grow maybe three to five feet a year. And alongside, we plant rows of evergreen, like Blue Spruce and Norway Spruce, that grow slower, but probably will have a longer life. And that has been successful.”

Hord has also experimented with bio filters at his boar stud barn, which houses approximately 50 animals. He used field tile – the plastic tubes with holes normally used to drain soil. “We attached the field tile to the fans coming out of the building. We took the black, plastic tubes and created a small matrix – a trunk line with lines running off that.”

Before manure is applied on any of the Hord Livestock land, soil samples are taken and the manure is tested to make sure it falls within the recommendations of the Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan. Before manure is applied on any of the Hord Livestock land, soil samples are taken and the manure is tested to make sure it falls within the recommendations of the Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan. |

On top of the pipes, he placed a mixture of composted yard waste and wood chips. When the air came from the barn, it was forced through the field tile and up through composted materials. Although it proved successful in bringing down the odor, Hord doesn’t see it as a practical solution for a large-scale operation.

“But it was definitely an interesting experiment and I’m glad we did it,” he says. “Maybe the technology, and the experience of playing around with it, will help us in the future.”

Part of the environmental activism includes effective water and soil conversation practices. They have put in filter strips or grass waterways at all their locations. “We’ve done quite a few over the last four or five years and we will continue to add them as we buy farms or take over farms,” says Hord.

The filters are created by seeding different types of grasses along the waterways. The farm works through the county soil and water office that helps share in the cost of planting.

“There are different programs, and incentives,” explains Hord. “We lease the waterways into these government programs. They pay us a certain amount to leave that land idle, but we aren’t driven by the money. It’s just good environmental practice to have these filter strips around these waterways. They slow down erosion as they filter nutrients.

“It’s been shown that a lot of nutrients will attach themselves to dirt particles. So if you can prevent them from washing away, that really helps,” he adds.

To ensure manure application is done correctly and the rates are precise, the Hord team uses a GPS system. To ensure manure application is done correctly and the rates are precise, the Hord team uses a GPS system. |

Although being an active steward of the land is important, Hord Livestock knows that’s not enough. A vital piece of the puzzle is to also communicate and promote their operation and make sure people are informed. A little over a year ago, Hord’s Livestock began publishing a one-page neighborhood newsletter that goes out to adjacent farms and homes.

“We think it’s important that our neighbors understand what we’re doing,” explains Hord. “We cover a lot of things – manure application, animal handling, and other timely information. And we usually put a recipe for pork in there.”

Hord Livestock also has a website, www.hordlivestock.com. It’s another place where people can find out more about the company’s history, employees, mission, as well as its different operations.

“We use it for overall general promotion of our farm as well as for recruiting. And it’s been a good tool for us,” says Hord.

From the farm’s start in 1946, to its large-scale operation today, one thing has remained consistent – a serious commitment to the land and its animals. And that commitment is turning out to be recipe for success.