News

Agronomy

Environment

Field Crops

Production

Research

Sustainability

Maximizing the Value of Nitrogen

Manure nitrogen can be a valuable crop nutrient when conserved and managed.

September 9, 2016 by Dr. Deanne Meyer

What happens to the excreted nitrogen?

What happens to the excreted nitrogen?

It’s summer and temperatures often break the 100 degree Fahrenheit mark. No doubt, we still have a few days before fall when the temperatures will go beyond 100.

Why would I be thinking about temperature and nitrogen management at the same time? My simple answer is that manure nitrogen can be a valuable crop nutrient when conserved and managed. Temperature plays a part in that.

The crude protein concentration in diets is formulated to provide nitrogen and amino acids for animal production and growth. Diets with concentrations greater than needed result in animals excreting more nitrogen. Diets with concentrations less than needed may result in reduced production (less milk made or lower growth rates). Targeting formulations to animal needs has the greatest potential to optimize nitrogen use efficiency.

Data from feed inventory analysis on seven commercial dairies in California identified that 16 to 27 percent of total nitrogen in feedstuffs delivered to the facility were recovered in milk and animal tissue (growth). The other 84 to 73 percent of nitrogen was assumed excreted. For 100 pounds of nitrogen fed to these dairy herds (all replacements were reared on-site), roughly 73 to 84 pounds would be excreted.

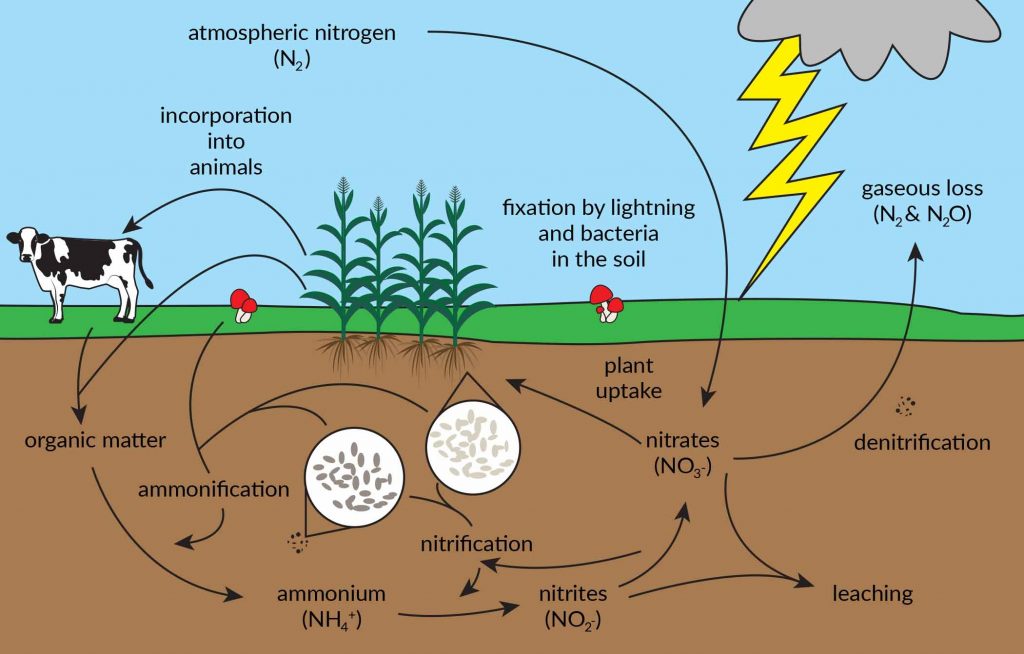

What happens to the excreted nitrogen? That depends on the animal housing and manure collection/storage process. Most of the nitrogen excreted by dairy animals is in the organic form. Let’s look at the highlights of the nitrogen cycle. Organic nitrogen needs to be mineralized to ammonium, a plant available form of nitrogen. It’s not particularly mobile. It clings to negatively charged particles including clay. It may also off gas to the atmosphere as ammonia. Or, ammonium may be converted to nitrite and nitrate through nitrification. Nitrate is also plant available. Unfortunately, since nitrate has the same negative charge as most soil particles, it does not cling to soil particles. In fact, it leaches easily when excess rain or irrigation water is applied. Nitrate may be fully denitrified and leave the solid/liquid system as N2 gas. This colorless, odorless gas makes up about 78 percent of the air we breathe. Microbes and enzymes present in the soil are responsible for nitrogen metabolism.

Most nitrogen in manure is in the organic fraction. The fact that it’s organically bound is great for the soil, as organic amendments are a great way to help build up soil organic matter content. However, the timing of availability of organic nitrogen is not as predictable as we’d like it to be in order to manage crop nutrient needs based on organic nitrogen applications.

Urea is the next largest form of nitrogen excreted in cattle urine. Urea is no stranger in farming. In fact, synthetic urea is used as a fertilizer. When entering the dairy manure stream, urea is often hydrolyzed to ammonium (if in a moist or wet environment) and then either volatilized as ammonia or it stays in solution. Ammonium in liquid manure is plant available. Ammonium will volatilize. Volatilization increases as pH, temperature, and wind speeds increase. Site-specific conditions, including management, impact how much ammonia is volatilized. When liquid manure is managed to conserve nitrogen, the next step is to manage it to minimize losses. Ammonium can undergo nitrification to nitrate after land application. Matching application timing and rate to crop needs is key to be efficient with nitrogen incorporation into plant matter and not lost to the environment. The nitrification process requires an oxygen rich environment [note: very few dairy lagoons in California would promote nitrification within the lagoon]. Ammonium may also remain adhered to soil particles. Under our hot summer conditions, urea in open lots may not hydrolyze as the moisture rapidly dissipates. Urea that hydrolyzes in open lots will likely volatilize as ammonia.

Rapid drying of open lot feces and urine has the greatest potential to conserve nitrogen. Keeping corrals dry and well managed will minimize pockets of wet material. Some operators harrow daily to break up clods and aid in drying. This is helpful to reduce fly populations as well as conserve urinary nitrogen. Management of solid manure through active composting is great to reduce microbial populations present, however it will result in loss of ammonium as piles are turned and rewetted. Flush systems regularly collect feces and urine from concrete lanes and transfer the material to a liquid storage/treatment structure. Urea is hydrolyzed and ends up in the liquid system as ammonium. The amount of this volatilized to the atmosphere will depend on wind speed, pH, temperature, and exposure surface. If you actually smell ammonia at the bank of a lagoon, you might want to check the pH and see what modifications are possible to lower the pH to something closer to seven.

First, identify what you expect the technology to accomplish (its job description) before you ask any questions about the technology. If you want a technology that removes solids from a liquid waste stream there are many different types and they all function a bit differently. If this is your focus, carefully evaluate your bedding source, amount used and particle size length. Experience shows us that particle length of different bedding sources varies, resulting in big differences in how separators or technologies work from dairy to dairy. Alternatively, if you want a technology that reduces the amount of nitrogen you emit to the atmosphere from your manure treatment/storage area, then perhaps you’re considering monitoring and management of pH, temperature, and wind speed. Transferring nitrogen from the liquid to the solid phase opens up greater opportunities for nitrogen exports.

Carefully identify the job description and expectations (manure function, employee labor, etc.) of any new management practice or technology before you consider it for your facility. Do your due diligence with air and water regulatory agencies before considering purchase and installation.

Yes, the nitrogen cycle is complex. Yes, nitrogen is very important to manage in order to maintain groundwater quality. Yes, there are things one can do. First, talk with your dairy nutritionist to be sure you’re not over feeding nitrogen to your animals. Second, evaluate manure handling to optimize nitrogen conservation once excreted. Keep solids in corrals dry in summer. Regularly flush lanes to collect and contain urea/ammonium nitrogen. Third, talk with your crop consultant about organic nitrogen variability.

Dr. Deanne Meyer is a livestock waste management specialist in the department of animal science at the University of

California – Davis.