Features

Applications

Swine

Variety of manure management practices

April 3, 2008 by Tony Kryzanowski

Due

to the size and dispersed nature of its facilities, the Heimerl hog

operation in Ohio uses a variety of manure management practices—from

manure injection to a traveling irrigation gun—to do the job right.

Due to the size and dispersed nature of its facilities, the Heimerl hog operation in Ohio uses a variety of manure management practices—from manure injection to a traveling irrigation gun—to do the job right.

If wine were swine, Jim Heimerl would be raising vintage grade hogs. However, the challenges associated with managing the manure generated by these well-heeled hogs are no less than the challenges commonly experienced with market grade hogs. In fact, it is a bit more challenging due to bio-security and—because of his location—urban sprawl issues.

Ohio-based Heimerl Farms raises 7,500 sows on contract as multipliers for swine genetics company, PIC International. It also finishes 2,500 hogs on a separate contract for another hog farmer. “We are breeding the grandparents of the hogs that represent the market animals for the hog industry in the United States,” says Heimerl. “About 48 percent of the pork chops out there in the US come from a PIC genetic background.”

Since the Heimerls are heavily invested in breeding pedigreed sows, their facilities on the home farm, as well as three separate hog production locations elsewhere in Ohio, must be bio-secure. This includes shower facilities for staff entering and leaving each barn. As an additional bio-security measure, all equipment associated with manure management must be cleaned and disinfected before it is allowed onto a Heimerl farm site. That’s because the multiplier sows must be free of any major disease such as Porcine Respiratory Reproductive Syndrome (PRRS), which has infected up to 70 percent of the hogs in the US.

About 50 percent of the cropland Heimerl Farms has under cultivation has manure applied as a form of fertilizer. They have realized significant financial benefits from using manure versus purchasing high-priced commercial fertilizer. About 50 percent of the cropland Heimerl Farms has under cultivation has manure applied as a form of fertilizer. They have realized significant financial benefits from using manure versus purchasing high-priced commercial fertilizer.

|

When asked why he opted for this niche area of hog production, Heimerl says it seemed like a logical step considering how he and his wife, Kathy, intended to manage the operation. It was their intention to operate as bio-secure as possible regardless of whether the farm raised pedigreed or market hogs. “We thought if we were going to go to that extent, then we might as well try to get some added benefit from the premium offered in raising breeding stock,” he says.

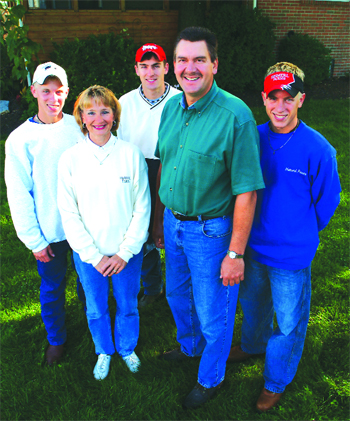

The Heimerl family traces its roots back to farming in the Licking County area of Ohio near Johnstown to the 1940s. Jim and Kathy took over in 1980 from Jim’s parents, and they are working hard to keep it a family business. The couple’s three sons are interested in joining the operation.

Given the increase in population density, the problems related to urban sprawl have complicated both the company’s bio-security need and manure management practices. For example, the Heimerls established their Eagle Creek Swine project 135 miles from their home base in a sparsely populated area of Brown County,

Ohio in 2000. Since then, more than a dozen new homes have been built near the hog operation. This type of pressure is becoming a significant challenge to farmers with historical roots in rural areas of the country, areas that are now becoming heavily populated. The migration to the country in some areas has the added complication of driving up land prices.

One significant impact the sudden influx of new neighbors has had on the design of the Heimerl facilities is that they have opted for deep pits for effluent storage under slatted floors in their barns, instead of the typical two-foot deep shallow holding pits, with the effluent then pumped into nearby lagoons. “It’s a case of ‘out of sight, out of smell’,” Jim says. “People can smell a lot with their eyes.” The pits range between eight to 10 feet deep.

Jim and Kathy Heimerl of Heimerl Farms with sons Matt, Brad and Jeff, who are interested in joining the farming operation. Jim and Kathy Heimerl of Heimerl Farms with sons Matt, Brad and Jeff, who are interested in joining the farming operation. |

While the Heimerls’ home place is in Licking County, they operate their pedigreed facilities at locations 30, 60 and 135 miles from home. Each location finishes 2,400 sows. They each generate about 900,000 gallons of manure effluent per year. Of their total 35 finishing barns, about 30 are equipped with deep pits.

The Eagle Creek facility is equipped with a lagoon that is aerated using a Balzer pump. In the family’s ongoing effort to remain a neighbor-friendly hog producer, the Heimerls use chopped straw in a layer three to six inches thick in the lagoon as an effective odor deterrent. The straw forms a crust and holds the odor down. They have also tried additives to manure effluent to both reduce solid content and odor, with limited success.

In terms of aesthetic appearance, they have made a conscious effort to build soil mounds as a visual barrier and have planted trees, scrubs and green areas in the vicinity of buildings.

Due to the size and dispersed nature of their pork finishing facilities, the Heimerls use a variety of manure management practices. This includes contracting the services of manure disposal contractors, contracting tanker trucks with injectors to inject the manure on some of the 2,600 acres of cropland the family manages, application of manure using a flexible drag hose system, or land application using a hard hose and traveling gun irrigation system. One of the critical aspects of establishing their business at Eagle Creek was negotiating long-term manure application agreements with local landowners.

The manure effluent is typically pumped into Houle tanker trucks equipped with Balzer injectors for application on land at this particular location because of the area’s heavy clay soils. This is because these soils won’t accept large volumes of effluent. So using anything other than injection would raise concerns about possible run-off from the hills.

As an extra security measure, the Heimerls have installed a catch pond at the Eagle Creek production site in the unlikely event of a breach or effluent spill. As a freshwater source, the water is used for wash water and in their evaporative cooling cells. It has also attracted wildlife from geese and ducks to wild turkeys.

By far, the majority of the manure effluent collected in the Heimerl’s hog production activities is spread in the fall using a Farmstar traveling flexible drag hose system with a Doda pump.

They contract the services of a soil sampling company that conducts Global Positioning System (GPS) grid sampling, particularly on their own farmland. It serves two purposes. The first is to calculate manure application rates based on the nutrient composition of the soil. The sampling is done approximately every three years in two-acre grid increments. The second reason is to gather benchmarking information as a form of insurance to demonstrate the impact that manure application is having on the soil.

“If any more regulations come down, we can show the regulators where we are in terms of nutrient content and if new regulations come in five years, we can show them what we have done and how it has impacted on the soil,” says Heimerl. At the moment, he says it is unknown what new regulations may be on the horizon, but phosphorus content is a big concern.

“That’s what we think they will be looking for because phosphorus is not a leachable mineral,” he says. The Heimerls regularly use phytase to cut down phosphorus levels in the manure generated by their hog production.

Heimerl says about 50 percent of the cropland the farm has under cultivation has manure applied as a form of fertilizer, and they have realized a significant financial benefit from using the manure in this way. “I know that an application of about 6,000 to 7,000 gallons provides 100 percent of our phosphorous and potassium needs on a 150-bushel corn crop on some of our farmland,” he says.

“It definitely has some commercial value to us.” He estimates that it generates about $45 per acre in savings by not having to purchase high-priced commercial fertilizer to obtain the same nutrient value on the cropland where the manure is applied.

About three-quarters of the manure is applied in fall. Recently enacted legislation in Ohio prohibits spreading of manure in wintertime on frozen ground. Heimerl says this means they just have to do a better job of planning fall and spring application.

Typically, they will use either tankers with injectors or their Hobbs hard hose and traveling irrigation gun system to spread the manure in spring in the event that a spring application is required.

In terms of the timing of application, Heimerl says they avoid spreading on weekends to keep good relations with neighbors and pay extra attention to water quality issues and application rates.

In recognition of the effort the Heimerls have put into both operating as good neighbors and protecting the environment, they were recognized with an Ohio Environmental Stewardship award in 2003 and as one of four national Environmental Stewards by the National Pork Board in 2004. A national selection committee chooses worthy stewards based on an evaluation that covers manure management, conservation practices, odor-control strategies, farm aesthetics and neighbor relations, wildlife habitat and innovative ideas.

When attempting to maintain a hog production business with people

crowding in all around you, it takes an operation of this caliber to successfully avoid the health and public relations nightmares that can sometimes develop when city folk get an itch to move to the country.