Features

Research

The benefit of good germs

Studies from the USDA-ARS show improved health in broiler chickens housed on used litter.

January 11, 2021 by Ronda Payne

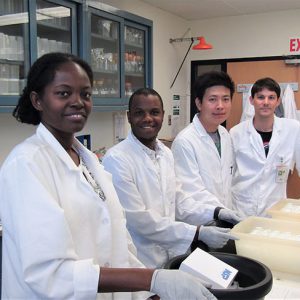

Five- to six-week old Cobb-500 broiler chickens on reused litter. Photos courtesy of Adelumola Oladeinde, USDA-ARS.

Five- to six-week old Cobb-500 broiler chickens on reused litter. Photos courtesy of Adelumola Oladeinde, USDA-ARS. A fresher, cleaner environment is better when it comes to livestock health, right? Not so fast. Science is challenging this widely accepted theory.

Recent studies exploring used bedding litter, micro-organisms and broiler chicken health are bringing the need to sanitize barns between flocks into question. The notion that kids who eat dirt will develop healthier immune systems is similar to the research findings around the properties of reused litter. This relationship between good and bad gut bacteria is commonly understood in humans and it seems that broiler chicken litter develops a comparable microbiome over time, where good organisms can keep the bad ones (like Salmonella) in check and thereby improve the health of broilers.

The pair of studies out of the United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS), in collaboration with researchers at Colorado State University, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) and the University of Georgia’s department of poultry science, explored how aged chicken litter with certain bacteria and other organisms can influence broiler health and impact harmful pathogens. Back in 2017, when researchers began looking into reused litter, the belief was that Salmonella would become immune to the beneficial bacteria in reused litter and grow stronger than its ancestor strains.

Adelumola Oladeinde, research microbiologist in the bacterial epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance research unit with the U.S. National Poultry Research Center of the USDA-ARS, says the initial hypothesis was that cleaner litter meant healthier birds. However, he found this wasn’t the case.

“Old litter is better than new. I think the key is the type of bugs. It’s not just the volume, but the volume and type (diversity) of bugs,” he says. “The bugs from reused litter seem to be hardy and have, over time, established the repertoire of tools needed to thrive in the broiler chicken house. They are better competitors.”

This sense of thriving means that the bacteria evolves over time, builds up and is able to break down chicken feeds and additives present in feed, survive the harsh environment of the broiler barn (temperatures, pH, humidity) and break down antibiotics and disinfectants. Chicks that live with these beneficial bugs can become inoculated with them, as they naturally peck at and eat litter, which increases the likelihood of the chicks having greater immunity. Mortality rates in chicks introduced to a reused litter environment are about the same as – and may potentially be lower than – those placed in a clean litter environment.

“We did not observe higher mortality,” Oladeinde says. “For birds raised on fresh litter, mortality was four percent after 49 days, 2.8 percent after 49 days for reused litter one flock old, 2.4 percent after 49 days for reused litter two flocks old and less than one percent after 35 days for reused litter three flocks old.”

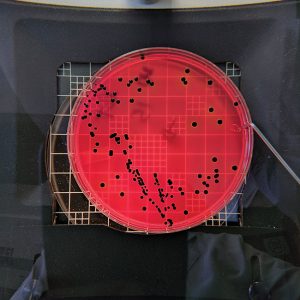

In the studies, researchers collected used bedding litter samples from the university’s poultry research center, measured each sample’s microbial characteristics and then added Salmonella to the mix. Samples were then measured on an ongoing basis to identify growth and change of the various characteristics.

Oladeinde found that the microbiome of reused litter can have the right moisture, ammonia, bacteria, fungi and viruses to keep Salmonella from establishing and becoming a health issue to broilers. But the right balance is important for beneficial bacteria to thrive. For example, two groups of bacteria, Bacillaceae and Actinobacteria, are major players in reused litter that produce antimicrobials. They need to be established prior to placing the flock and will contribute to the overall microbiome health.

“Reused litter microbiome is ‘predictable’ under raised-without-antibiotic broiler chicken production,” he says. “Broiler chicks raised on reused litter carry less antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg after two weeks of oral gavage.”

He adds that acid exposure gives the Salmonella strain antimicrobial and virulence resistance to the beneficial organisms. Thus, pH levels have an important role in the litter microbiome’s traits and therefore the broilers’ health. Acidic pH levels of less than 4.5, or alkaline pH levels of more than 9, are too extreme to maintain a health-benefiting microbiome.

“Efforts should be made to keep litter pH neutral and extending the litter downtime should help reduce E. coli numbers in reused litter,” Oladeinde says.

Litter downtime – the waiting period between flocks – should be more than 14 days as, during the study, the microbiome became unfavorable to Salmonella after two weeks. In a practical on-farm setting, it’s important for a farmer to understand the age of the litter prior to placing chicks, as the litter pH increases with the number of flocks on it, and adjustments shouldn’t be made once a flock is placed. Alternatively, downtime could be reduced if desired pH and healthy organism levels are achieved sooner. It’s best to check pH levels prior to placement and after downtime.

“For our studies, we left the litter undisturbed after birds were removed and monitored the litter weekly for two to four weeks,” Oladeinde says. “After this downtime period, we applied sodium bisulphate on the litter 24 hours before chicks were placed. We did this from flock to flock for four flocks.”

Acid-based amendments like sodium bisulphate can bring the pH level down while also improving the odors associated with ammonia. However, as reused litter ages and absorbs more ammonia, these types of treatments may become cost-prohibitive to achieve the right pH levels. Oladeinde recommends starting with fresh litter at this point. Mixing fresh litter with reused is currently being explored, as is a study to reproduce the same results of a litter microbiome that reduces Salmonella strains.

While there may be cost savings from reusing litter from flock to flock, these must be considered with the offset of required amendments. The overall benefit should not be about cost reduction but about better overall health of broilers, which could lead to a lower average mortality rate and better meat that may make for a better operation, better reputation and potentially long-term financial gain.

In the future, it may be possible to further identify the types of bacteria doing the heavy lifting in the microbiome of the litter to create applications that would directly contribute to improved chicken gut health. One such example is what Oladeinde calls “pro-litter-biotics” – probiotics created from birds raised on reused litter. This concept is undergoing testing, with results expected in 2021.