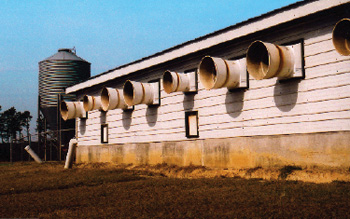

North Carolina hog operation

Bobcat Farms works diligently to properly manage and fully utilize its

manure—and take care of details, small and large—using Best Management

Practices as guiding principles.

North Carolina hog operation Bobcat Farms works diligently to properly manage and fully utilize its manure—and take care of details, small and large—using Best Management Practices as guiding principles.

Running a successful farm operation often comes down to taking care of the details, both small and large.

Henry Moore III (left, in photo) and Alan Williams of North Carolina’s Bobcat Farms. Henry Moore III (left, in photo) and Alan Williams of North Carolina’s Bobcat Farms. |

When it comes to the overall management of their hog operation—and the manure management aspects in particular—Henry Moore III says they work to take care of those details, using Best Management Practices as guiding principles. “It’s a good benchmark for our operation,” says Moore, president of family-owned Bobcat Farms.

Along with colleague Alan Williams, Moore oversees a family partnership consisting of a 5,000 sow-to-wean farm, an 8,800-head gilt development facility, and—just to round things out—a 150-head Angus cow/calf operation near the town of Clinton, North Carolina.

Moore, a graduate of NC State in business and animal sciences, is also an owner/grower with Coastal Plains Pork, which markets over 500,000 slaughter hogs annually. He was, in fact, one of the founding members of Coastal Plains Pork. The company is made up of a small group of hog operations who have partnered together to raise and sell hogs, much of them to Tyson Foods.

While his father, Henry Moore II, does not take a hands-on role in the business these days, he was instrumental in getting Bobcat Farms started in 1992. His timing could not have been better with Bobcat Farms, as the hog industry took off in the 1990s. He worked hard to raise the capital to start the farm, seeing it as an opportunity to make the transition into a different end of the ag industry for both himself and his son, both of whom were aerial applicators at that time. Father and son still practice aerial application with their Weatherly plane, which is powered by a 450 horsepower radial engine, though that is mostly on blueberries and their own crops at Bobcat Farms these days.

From the start, Moore and Williams have taken to managing Bobcat Farms with a high degree of professionalism—and technology. They opt to utilize PDAs and PCs, rather than pad and pencil, for record keeping.

“If we were out there pumping in our fields today for ten hours, we could write down the numbers, bring them into the office and then do the calculations,” says Moore. “But with the PDA, as soon as you’re done with an application, you punch the information in and it tells you how much nitrogen you’ve got left and it brings you up to speed on your phosphorus. It keeps current with your last lagoon samples and your soil samples. It’s a great system.”

Implementing this system was an evolution, rather than revolution, for Bobcat Farms. When they were a contract growing operation, they operated a similar system for breeding.

They’ve worked hard to be progressive at Bobcat Farms, both in general farm operations, and with manure management. The farm was selected to be a pilot farm for the North Carolina Environment Management System. “It’s my belief that we’ve got to continue to improve our manure management techniques,” says Moore. “It’s going to continue to be one of the major concerns facing hog producers.”

Manure samples are taken every 90 days, and soil samples are done annually at Bobcat Farms, with the goal in mind of making maximum use of their hog manure as a nutrient. “This is not great land, so we really need the nutrients in the manure to grow good crops,” explains Moore. “If we had to buy commercial fertilizer for everything, we couldn’t afford to maintain our cow herd and would be better off to sell the cows and let someone else tend the land.”

Utilizing the manure is a great fit for them. In addition to the water aspect of the manure that is beneficial to the land in the summer, the contents of the manure, especially the nitrogen, are all beneficial to the forage they grow for their cattle. “And we’re lucky in that we have plenty of land for applying manure,” adds Moore. Of their 500 acres, 350 acres of it is used for their cattle program. What they have in place now is a manure model that works for them, notes Moore.

In addition to its hog operation, Bobcat Farms also has a 150-head Angus cow/calf operation. In addition to its hog operation, Bobcat Farms also has a 150-head Angus cow/calf operation. |

But, of course, there are other methods. The much-talked about hog manure recommendations from Dr Mike Williams look at using the manure in much different ways, involving treatment and processing. Williams has directed the four-year-old, $17.3 million effort between the state of North Carolina and pork industry partners to identify and quantify alternative swine waste management technologies.

Many in the North Carolina hog industry—including Moore—find the recommendations interesting, but wonder if they are practical. “These are alternatives, but are they economically feasible? The other question is are they really any better than what we are doing now? I don’t know that they are. What we are doing now, taking effluent from the lagoon and applying it to our land, is probably the best use for us and our operation. What has been recommended may work for other hog operations, but our system works for us.” Going to a vastly different manure management system would mean changing their business model, and perhaps letting go of the cow/calf operation.

The manure management alternatives suggested by Williams, and others, need to be examined carefully, Moore notes. “You could install a separation system, do some composting and make it into pelletized fertilizer, but you’ve got to have markets for that product.” For some operations there may be a local market for compost, but for others, there may not be.

“Do I want to go and spend a large amount of money for a separator and new technology producing compost for a market that may or may not be there? I know what I have now works. That doesn’t mean we won’t look at making changes or improvements. But we’re not going to jump on to just anything.”

At Bobcat Farms, they have well-established procedures for manure application, and what follows. Once manure effluent has been applied, they have a 35-day waiting period when no harvesting is carried out. “That’s not the law, that’s just our rule of thumb,” notes Moore. “We generally like to apply the effluent, and then have at least one good rain shower that will incorporate the effluent and get the full benefit from it as a nutrient.”

Application is beneficial for all their field production, but seems especially beneficial for their coastal hay. “It doesn’t take long to get into the system. If we irrigate today, we can see a big difference in a week’s time. It really affects production dramatically.”

For application, Bobcat Farms uses two Hobbs Reel Rain reels, each four inches. The slurry is turbine powered, so there are no additional fuel costs, such as gas, or repairs to external motors. The Reel Rain traveler irrigation systems are manufactured by Amadas Industries, based in Suffolk, Virginia. Supplying Bobcat with the system, and parts and service, is local dealer Rainman Irrigation of Mount Olive, North Carolina.

Reel Rain offers a wide selection of models to choose from, with hose sizes ranging from 2.5 inches in diameter to five inches, and lengths from 700 feet through 1,500 feet. It has a wide variety of drive systems including water turbine, slurry turbine, gas mechanical, and gas hydrostatic, which are available on most Reel Rain models.

Initially, Bobcat Farms relied completely on the aboveground irrigation system, an approach that was effective, but not very efficient, Moore notes. “You could have two or three guys out there spending all day moving irrigation pipe. When we got the farm going and on its feet, we put in underground irrigation.” They now have about 12,000 feet of six-inch underground pipe, with four-inch risers, for the reel system to connect to, which makes the reel system more manageable.

The fields are designed to maximize manure application and coverage. However, there are areas that the irrigation system doesn’t reach, and small amounts of commercial fertilizer are purchased and applied to these further reaches of acreage. “That’s fine, but the problem in that situation is that there is no water, and we need the water for the sandy soil we have.”

To maximize the use of the manure effluent over the entire acreage, they installed a 2,000-foot trunk line last summer that runs from the finishing facility to the sow farm. They were not getting enough lagoon water at the finishing facility, mostly due to new technology installed in the barns that resulted in more efficient water use. Plus, they also wanted more effluent at the second site to irrigate a recently cleared piece of land on which they’re now growing corn and small grains.

Managing its three lagoons, two with 10 million-gallon capacities, and one with a 12 million capacity, is key to the success of Bobcat’s overall manure management program, says Henry Moore, noting that the lagoons are monitored carefully. Managing its three lagoons, two with 10 million-gallon capacities, and one with a 12 million capacity, is key to the success of Bobcat’s overall manure management program, says Henry Moore, noting that the lagoons are monitored carefully. |

Bobcat Farms has three lagoons, two with 10 million-gallon capacities, and one with a 12 million capacity, from which the effluent is pumped using two Rainbow lagoon pumps, powered by 110 and 130 horsepower John Deere motors.

Managing the lagoons properly is key to the success of their overall manure management program, says Moore, noting that the lagoons are monitored carefully. Lagoon odor has never been an issue for the farm. “We’re far enough off the main road and away from any neighbors that it’s not a problem. It’s never been an issue for us and we often tell people, ‘If you smell our hog farm you are trespassing.’”

It’s clearly a system that has worked well for them, says Moore. “The lagoon system is great, the anaerobic side of it has always been really active. We look for the bright pink color and as long as that’s there, we know the lagoons are working properly.”

And they want to keep it that way. They are careful, if not wary, about using too much detergent or anti-bacterial materials in the barns. “You may be helping out one side of the farm in trying to keep disease down, but you could end up killing the other side, the manure and application side, because you’re affecting all the good bacteria in the lagoon.”

The farm’s approach of principally relying on manure for nutrient management has been a solid move, especially considering the recent price increases for commercial fertilizer. They don’t need to add much of anything, except for some potash occasionally. “And we lime the land every year,” adds Moore. GPS mapping is done at the same time as soil samples are taken. “That way when we lime it, we can be more precise in terms of placing it.”

Right now, Bobcat Farm is pretty close to where they want to be in terms of manure management. Any problems they have are of a generally minor nature. On one part of their acreage, they can have a problem with a grass called goose grass. “If an area gets too damp and doesn’t dry properly, that goose grass really comes up. We are careful about how much liquid we put down, and letting it dry.” Beyond that, it’s pretty much a cycle. “We’ll cut the hay, and we pretty much know that we need to be applying some manure effluent within four or five days for both water value and nutrient value.”

Unlike some other hog operations, which struggle in terms of finding land to apply their effluent, Bobcat Farms could, in fact, use more effluent. They have some forage land in need of extra nutrients, Moore notes. These needs may be met with solids from their oldest lagoons if the metals content is reasonable.

Bobcat Farms currently has things pretty well nailed in terms of overall farm management. That said, Moore would not rule out some expansion a few years down the road. That’s likely to be on the cattle side, rather than with the hogs.

In terms of changes on the manure side, Moore says he’d be interested in looking at lagoon covers, and generating some power from the methane from the manure, provided that’s economically practical. They might, in turn, be able to generate some greenhouse gas credits. “It would be a real bonus.”

Over the last decade, the hog industry has been under incredible scrutiny in North Carolina, even with a moratorium on the development of more hog farms. While that may be lifted, Moore suspects the level of scrutiny is unlikely to change.

“The critics who don’t like how we operate are going to continue to disagree with our methods, no matter how good we are at manure management or the small number of spills the industry may have.” And that is the case despite the fact that the amount of spilled treated waste from hog farms is a mere fraction of the millions of gallons of waste—untreated—that municipal water systems release every year. “The ratio is probably one to 1,000 when you compare the hog industry to municipal operations,” says Moore.

Moore believes critics need to look at the hog industry’s record in recent years. “We’ve had very few spills and our impact on state waters is minimal.”

Any concern, he feels, should be focused on the municipal side. If the state were to be hit by major hurricanes in the future, there could be problems with some lagoons, but they would likely be minor. “The real problem would be with the city municipalities spilling over. Preventing devastation that a storm such as Hurricane Katrina brings would be a challenge, but hog producers today are good stewards and utilize their Best Management Practices to minimize the impacts.”