Installing a digester—and accompanying generator unit—has cut electrical costs for California’s Van Ommering Dairy and opened up some possible new business opportunities.

Installing a digester—and

accompanying generator unit—has cut electrical costs for California’s

Van Ommering Dairy and opened up some possible new business

opportunities.

Ever since a high school physics class planted the seed 25 years ago, southern California dairymanRob Van Ommering has thought about building a digester to handle dairy manure. Although he and his brother, Dave, finished construction on a plug-flow digester late last year and it’s now fully operational on their Lakeside, California dairy, his vision is far from complete.

The family-owned and operated Van Ommering Dairy, which milks about 500 head twice daily, is the most southwestern dairy in the United States and only about 30 miles east of downtown San Diego. The family-owned and operated Van Ommering Dairy, which milks about 500 head twice daily, is the most southwestern dairy in the United States and only about 30 miles east of downtown San Diego.

|

The dairy will finish building a covered freestall barn in spring 2006 that will make manure management more efficient. And Rob Van Ommering hopes to eventually build a new milking parlor closer to the generator to take advantage of surplus electricity.

But to really make the digester pay economically, he envisions joint ventures, such as a fishing pond, hydroponic greenhouses, aquaculture or providing electricity to industries with a small footprint, such as a radio broadcasting tower. “I figure if we were to zero-out our electricity bill by running wires to our major barns, wells and our shop—at best it would be an eight-year payback,” Rob Van Ommering says. “The way we’re going, it’s going to be 15 to 17 years.

“Right now, we’re only cutting our electric bill in half. But if you get some other avenues of income off of it, you’re in better shape.”

The family-owned-and-operated Van Ommering Dairy, which milks about 500-head twice daily, is the southwestern most dairy in the United States and only about 30 miles east of downtown San Diego. But relocating to a less-urban area is not an option, Van Ommering says. “My mother and sister-in-law have been doing dairy tours for kids in our area for 13 years,” he says. “We have a pumpkin patch in October that draws over 5,000 children. So we are kind of leaning towards ag tourism to augment our dairy income. We are only one of five dairies left in the county, so we figure we could retail some dairy products in the future.”

With the drylot system that the dairy has used for the past 45 years, workers clean the corrals on a quarterly basis. Then they would haul the manure to a neighbor’s farm and use it to raise oat hay. Some of it also is used by a vermiculture operation. The neighboring farmer has since lost his lease, so the dairy had to find another outlet for its manure.

California has some of the nation’s strictest environmental regulations, and many counties—especially those near urban areas—have even more stringent ones. Van Ommering only saw them growing more restrictive and began thinking the time was right to build a digester shortly after the new millennium.

“In 2001, [the USDA] added the grant program and then the state added the grant program to encourage things,” Van Ommering says. “So at that point, particularly with the state grant money and with the way things were heading on the environmental front, we figured you had to be on pasture or have your cows in freestalls and build a digester.”

At the time, RCM Digesters Inc, the Berkeley, California, firm that Van Ommering hired to oversee the project, estimated the cost to be about $489,000 for a plug-flow digester system that would handle manure from 500 to 700 animals. Two grants—$244,000 from Western United Resources Development and $150,000 in cost-share funding from the US Department of Agriculture’s Environmental Quality Incentive Program—would have offset most of the expenses.

Because of delays, mostly surrounding obtaining county environmental permits, the price tag climbed to $900,000 by the time the digester project was completed in late 2004. During those 2-1/2 years, steel prices had doubled, and concrete prices had increased significantly.

Dirt work began in December 2003, and Astle Corp of Deer Creek, Minnesota, began the concrete work in March 2004. Adding to the already delayed project was an unseasonably wet spring in 2004. The arid San Diego region typically receives about 10 inches of rain annually. During 2004, the region received about 30 inches, with most of it in late winter and early spring.

The Van Ommering digester consists of a mixing chamber feeding into a 28-foot wide by 12-foot deep by 128-foot long digester with a 45-mil thick polypropylene cover. The system has a capacity of 43,000 cubic feet or 320,000 gallons. The Van Ommering digester consists of a mixing chamber feeding into a 28-foot wide by 12-foot deep by 128-foot long digester with a 45-mil thick polypropylene cover. The system has a capacity of 43,000 cubic feet or 320,000 gallons.

|

The digester system consists of a 28-foot-wide by 12-foot-long by 12-foot-deep mixing chamber feeding into a 28-foot-wide by 12-foot-deep by 128-foot-long digester with a 45-mil-thick polypropylene cover. The system has a capacity of 43,000 cubic feet or 320,000 gallons, says Pete Dalla-Betta, an environmental scientist with RCM Digesters.

Unlike some digesters, which are a cement pit in the ground, Van Ommering’s is a cement chamber built into the side of a foothill. One cargo container houses the biogas and hot-water equipment while an adjacent one houses the generator and electrical equipment.

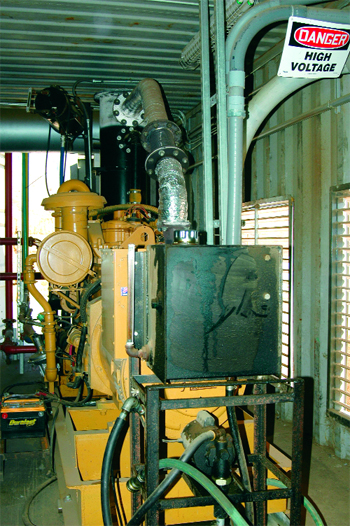

Biogas, currently comprising more than 70 percent methane, is collected and piped to a Cat 3406 generator installed by Martin Machinery LLC of Latham, Missouri. The system is designed to produce up to 60,000 cubic feet of biogas and generate up to 130 kW, Dalla-Betta says.

Van Ommering began filling the digester in June 2004, a long process because the dairy didn’t have much manure that wasn’t contaminated with dirt. He didn’t start heating the pit until March 2005, but by May 2005, the system was running off of the biogas it was producing.

Once the freestall barn is completed, workers will be able to scrape almost all of the manure daily and pump it to the digester’s mixing chamber. Until then, workers are vacuuming the manure two times per week from manger aprons holding 350 milking cows.

The digester is designed to handle about 10,000 gallons of fresh manure per day, but the dairy is currently only sending about 3,000 gallons daily. Until the freestall barns are completed, Van Ommering occasionally adds food oil and grease to stimulate biogas production and raise the methane concentration.

Although most experts recommend targeting about 11 percent to 13 percent solids, Van Ommering says that it is currently closer to 10 percent in his digester. “As dry as it is in southern California, just about year-round we have to liquefy the manure so that it will go into the vacuum tank and come out again,” he says. “We spray water onto the manger apron with a water truck before using the vacuum trailer. With covered freestalls, we will probably still have to add some water before we scrape into the collection pit because a pump will have to lift it 50 feet to the digester’s mixing tank.”

Even with the digester, Van Ommering will still have to handle solids. With composting, he says he could typically expect a 30 percent reduction in solids. With the digester, it may increase to a 50 percent reduction. “We will still have a lot of product to sell or dispose of, and we’re looking at some options,” he says.

One might be to sell it to the California Department of Transportation to use instead of hydroseeding. “In Texas and Georgia, they’ve shown that compost is more efficient in getting the vegetation to grow,” Van Ommering says. Another potential market may be area nurseries or organic farmers.

The digester liquid that comes off of the screw press will be used to irrigate the dairy’s 12 acres of pasture. And he’s exploring building a small treatment plant to reduce the nitrate and phosphorus content. Then the water could be used for a private fishing lake or possibly to grow hydroponic vegetables.

Under California Assembly Bill 2228, the Dairy Power Production Program, dairies receive a partial credit for the difference between electricity supplied to them through the power grid and electricity they generate and feed into the grid during a 12-month period. But they don’t receive credit for any excess

electricity generated above what they consume.

“A digester isn’t going to pay for itself in California the way the laws are set up,” Van Ommering says. “Our electricity bill is only cut in half at best, and we’re producing more than we’re consuming.”

Biogas, comprising more than 70 percent methane, is collected and piped to a Caterpillar 3406 generator. The system is designed to produce up to 60,000 cubic feet of biogas and generate up to 130 Kw. Biogas, comprising more than 70 percent methane, is collected and piped to a Caterpillar 3406 generator. The system is designed to produce up to 60,000 cubic feet of biogas and generate up to 130 Kw. |

Currently, Van Ommering’s system produces an average 32,000 cubic feet of biogas and 70 kW, Dalla-Betta says.

The California net metering law requires San Diego Gas and Electric (SDG & E) to credit Van Ommering the electrical generation charge approved by the California Public Utility Commission (currently 7.5 cents per kW). But SDG&E charges him for distribution, transmission and other miscellaneous charges approved by the CPUC (currently about eight cents per kW) on power the dairy takes off the grid. The dairy’s typical monthly bill for electricity is about $5,000 before it receives a credit of about $2,400 per month.

“We haven’t hard-wired anything directly,” Van Ommering says. “Everything goes into the grid, and we take it off the grid. In the future, we hope to have a new milking parlor closer to the digester and be directly connected. There’s $2,000 per month savings by zeroing out the parlor’s electricity bill. That’s almost $25,000 per year savings if you hard-wire the parlor. That goes a long ways to speeding up the construction timetable.”

To make the system pencil out, Van Ommering plans to look into joint ventures where he could sell some of the digester’s byproducts. One possibility involves the 170-degree hot water, which could be used for laundry or aquaculture.

The surplus electricity could be sold to nearby industries with a small footprint, such as a radio station tower. Not too long before the digester was operational, a local radio station was looking for a new location, with nearby power, to build a tower.

The station would have needed 50 kW, which is about the same amount that the dairy has surplus. But the station’s project was too far along for the dairy to step in. If the timing had worked out, “That would have been the cat’s meow,”

Van Ommering says.