Low temperature (psychrophilic) in storage digesters have been used for

years in many temperate parts of the world – mainly developing

countries – as a way to treat human and livestock waste and provide

cooking fuel.

Low temperature (psychrophilic) in storage digesters have been used for years in many temperate parts of the world – mainly developing countries – as a way to treat human and livestock waste and provide cooking fuel. They are cheap to construct – just throw an impermeable cover over an existing manure pond or storage tank – and can help control odors and stop nitrification.

|

|

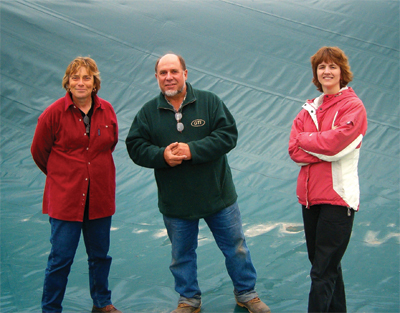

| (Left to right) Dr. Suzelle Barrington, a professor at McGill University, Claude DeGarie from Geomembrane Technologies Inc. (retired), and PhD student Susan King stand on the insulated floating membrane covering a manure storage tank at the Ferme Izalco swine operation, St. Francois Xavier, Quebec. Submitted photo |

In Canada, they have been slow to catch on, as it has been assumed that low temperature digestion is not effective. According to Quebec researcher Susan King, past trials of the system have been too short to show the benefits of the process and the microbial populations within the manure haven’t had an opportunity to acclimate to the psychrophilic conditions. She is currently conducting research that may change opinions about the usefulness of the system in Canada.

Environmental concerns

Environmental issues are one of the greatest challenges facing the Canadian pork industry. Complaints of nuisance odors and concerns about greenhouse gas emissions and nutrient management issues have increased as population densities grow in rural areas. There have also been serious problems in Quebec with cyanobacteria – blue-green algae – caused by eutrophication from agricultural nutrients entering waterways.

According to King, “Legislation and rules involving ammonia volatilization and nitrification issues are something important in Europe and will be coming to North America soon.”

King, a PhD student in the Department of Bioresource Engineering at McGill University in Quebec, is studying psychrophilic digestion at a commercial-scale swine operation located near St. Francois-Xavier, Quebec, in the Eastern townships by the Canada-U.S. border. The farm owner had decided to cover his existing manure storage tank as a way of controlling odor. A polymer membrane floating cover, designed by Geomembrane Technologies Inc. (GTI) of New Brunswick, was constructed on top of the 100-foot wide by 12-foot deep concrete storage tank. The tank’s sides were surrounded by soil and plastic pipes filled with concrete are used to keep the cover from lifting off the surface. Due to the abundant supply of electricity within the province of Quebec, there is currently no market for energy produced from biogas. The farmer has considered using the biogas in some capacity on the operation, such as a heat source for the barn during the winter months, but currently the methane that accumulates under the cover is vented.

Dr. Suzelle Barrington, a professor in the bioresource engineering department at McGill and King’s PhD supervisor, was looking for a site to study the development of anaerobic digestion under a cover. During her search, she contacted GTI, who directed her to the Quebec swine operation.

Research

King’s specific interest in the system involves the role played by microbial communities within the manure storage system and how quickly they can acclimate to different temperatures. She recently discussed her research during the First Annual Canadian Farm & Food Biogas Conference in Ontario, Canada.

When manure is excreted from swine, it has a temperature of about 39 Celsius (102 Fahrenheit). On the Quebec operation, the manure is collected in a pre-pit area for a few days before it enters the farm’s covered manure storage system, which has an average temperature range anywhere from between 0 to 20 Celsius (32 to 68 Fahrenheit). This can be a shock to the microbes that are naturally found within the manure and aid in its digestion.

“At first, it looks like they’re dead,” said King. “But they slowly acclimate to the temperature.”

She decided to study and confirm whether the microbial communities in swine manure can acclimate to a covered manure storage system and digest the swine manure within the tank.

“Previous laboratory work suggested that the microbial community in swine manure could develop a robust anaerobic digestion process given an acclimation time of at least 100 days,” she explained.

Using manure samples taken from the full-scale pilot site, King compared them to fresh manure right out of the pig and manure from an open manure storage tank. From the laboratory tests and solids analysis conducted, she was able to measure the ultimate methane potential for each sample, the methane production rate and the time required for the microbes to acclimate. Dr. Serge Guiot with the Department of Environmental Bioengineering at the Biotechnology Research Institute (BRI) in Montreal, Quebec, supervised her lab work.

According to King’s results, “A robust, acclimated microbial community is present in the pilot installation.”

In light of the development of this robust microbial community, the researchers decided to call the system In Storage Psychrophilic Anaerobic Digestion (ISPAD).

“The covered tank never goes above 35 Celsius (95 Fahrenheit) but the microbial community was very active,” said King. “Even at a temperature of 8 Celsius (46.5 Fahrenheit), the microbes in the covered storage manure sample keep right on producing methane with no lag time.”

This compares to the more than 450 days it took to acclimate the fresh manure sample and the one year it took for the open pit manure sample to acclimate at 8 Celsius (46.5 Fahrenheit).

Also with the ISPAD sample, 63 percent of the methane was extracted from the system and 24 percent of the manure solids were consumed. This compares favorably to the mid-temperature (mesophilic) digestion process, which results in 75 percent methane extracted and 50 percent of the solids consumed.

“This is close enough to say this is making a difference with what’s in your (manure) tank,” said King.

While microbes in the ISPAD tank, which had been in operation for three years, where fully acclimated, King suggests it would take no more than one year to acclimate the microbes if one covered an existing uncovered manure storage tank.

“This is because the microbes are partly adapted from being in the uncovered tank already,” she explained. “A brand new tank could take longer, though I can’t say for sure how long.”

Besides digesting manure solids and producing methane, King says other benefits of the ISPAD system include: slowing down the conversion of organic nitrogen to ammonia, settling out the manure’s phosphorous content and keeping rainwater from filling the storage tank.

“By eliminating the rainfall, that’s an extra meter of depth you don’t have to deal with,” she said.

Future research

King hopes to continue her research and examine nitrogen conservation and land application of manure from the ISPAD system, including wind tunnel tests to see what is released at application. She hopes to monitor two more swine production sites using covered manure tanks and optimize the ISPAD design.

“I don’t know what kind of pattern I’ll get with biogas production,” she said. “I just know we are producing methane.”

King’s research work at McGill was funded by Canada’s National Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), in cooperation with GTI and BRI.