People soon may view poultry litter in a whole new light — as an affordable alternative energy source.

About two years ago

People soon may view poultry litter in a whole new light — as an affordable alternative energy source.

About two years ago, the Propane Education and Research Council (PERC) funded a project to develop a continuous flow incinerator (versus a batch flow incinerator) to handle animal mortalities.

|

|

| Rem Engineering designed and developed the first commercial scale Ecoremedy solid-fuel gasifier. It was designed specifically for agricultural waste material. Contributed photo

|

The project was broken down into three phases, the first of which has been completed:

- Successfully incinerate poultry litter to produce steam.

- Adapt that system to burn mortalities. This step is currently in the testing phase.

- Create a system that can create steam from litter and mortalities. The steam can be used to run a turbine that creates energy that can be put onto the grid. This phase is currently on the drawing board.

|

|

| The Ecoremedy gasifier is mounted on a 48-foot-long, step-deck trailer, and combined with a Cleaver Brooks scotch marine boiler, creating a portable biomass-fueled steam plant. Contributed photo

|

Choosing the right partner

The first step in getting the project up and running was finding the right company to develop the technology to incinerate litter and produce energy. There was, however, a specific requirement of the technology — it had to be a continuous flow incinerator versus a batch system.

“The company that we found and felt had the technology was Rem Engineering,” says Paul Walker, a professor of animal science at Illinois State University (ISU), who headed up the project. “I’m not aware of any other continuous flow incinerators. They were the only ones that had the knowledge to make a continuous flow burner.”

Litter to steam

Once selected, Rem Engineering designed and developed the first commercial scale Ecoremedy™ solid fuel gasifier for testing and demonstration. It was designed specifically for agricultural waste material, including: animal tissue (offal and mortalities), poultry litter, animal manure and process sludge.

The team chose to test the Ecoremedy at Tyson Foods’ Bolivar feed mill in Fairmount, Ga., in March 2008. The mill operated 24 hours a day, five days a week and used natural gas to produce low-pressure steam (110 psig) for use in making 8,500 tons of feed pellets a week.

The portable unit was designed, built and tested over 11 months as litter was continually fed into the Ecoremedy and incinerated. The steam produced was used to produce the pellets.

|

|

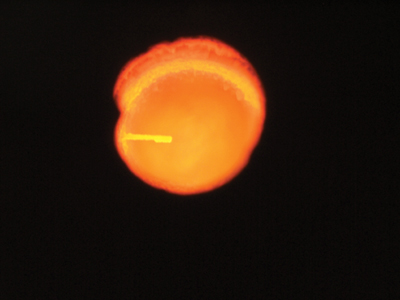

| The propane burner in the Ecoremedy is also used to preheat the gasifier, boiler and downstream equipment, as well as in the shutdown every week. Contributed photo

|

During the emissions testing portion, the team only used poultry litter, but they would also run intermittent tests using mortalities and other fuels as well. By early 2009, they knew the gasification system could be used to replace traditional fossil fuels such as natural gas and oil to generate steam for industrial use.

In addition to energy production, the team was also interested in the ash that was generated. With Rem’s system, the ash continually accumulates, and the team’s goal is for the ash to be used as a fertilizer.

A look at the Ecoremedy

The team mounted the Ecoremedy gasifier on a 48-foot-long, step-deck trailer, and, by combining it with a Cleaver Brooks scotch marine boiler, they created a portable biomass-fueled steam plant.

“We put a boiler on the front of it and the heat from the incinerator heats the boiler and produces steam,” explains Walker. “That steam was used to replace 20 percent of the steam required by the Tyson feed mill to produce pellets.”

To make sure they could burn the mortalities, a two MMBtu/hr Gordon Piatt propane burner was mounted through the ignition arch of the gasifier. The angle of the ignition arch directed the propane flame onto the pile for use when limited mortalities were conveyed through the gasifier.

“The poultry litter is exothermic,” says Walker. “It doesn’t require propane for burning, and without that supplement heat the incinerator can easily reach 1,500 degrees. But mortalities are different and require temperatures up to 2,500 degrees, especially if the plan is to destroy the prions that cause BSE.”

The propane burner was also used to preheat the gasifier, boiler and downstream equipment, as well as in the shutdown every week.

|

|

| There was great interest in the ash generated by the Ecoremedy. With Rem’s system, the ash continually accumulates, and, it’s hoped, can be used as a fertilizer. Contributed photo

|

Simple operation

Tyson says the machine was remarkably simple to operate. Solid fuel (primarily litter) was fed into the gasifier through a guillotine gate used to regulate the depth of the fuel bed. By changing the conveyor speed and fuel bed depth, the operator could control the load of the unit.

When there were changes in fuel, the force draft (FD) fan speed was adjusted to meet the gasification and combustion conditions within the system.

Ash from the gasifier discharged continually through a rotary airlock located in the center of the trailer and was then conveyed away from the trailer.

Results

Test results were positive across the board.

During the 120-hour workweek, the Ecoremedy generated an average of 1,400 lbs/hr of steam at 110 psig for the feed mill.

In addition to providing approxi-mately 20 percent of Tyson’s steam consumption, the ash created was tested and found to be below the limits set by the European Union (EU) using the TEQ metric established by the World Health Organization (WHO) for measuring dioxin and furan levels in animal feed. In short, the ash could be used globally as an all-natural fertilizer.

The Ecoremedy exceeded all design criteria when it came to gasifier performance, including:

- feed rate of 7.5 MMBtu/hr

- flow of 1,453 lbs/hr

- energy content of 3,627 Btu/lb

- temperatures exceeding 2,300 F

- uptime was nearly 100 percent

- one operator required per shift

- low carbon monoxide (CO) measurements —consistently less than 100 ppm — an indication that complete combustion of the biogas is occurring.

|

|

| For poultry operations, a permanent incinerator could be set up to burn through the litter routinely and to burn mortalities when necessary. Contributed photo

|

Alternative fuels

Although incinerating mortalities wasn’t the focus of the first phase of the project, mortalities were added to the litter at specific times. For example, 500 pounds of poultry (chick) mortality were fed into the gasifier over a four-hour period, creating a mix of 25 percent mortality and 75 percent litter. The Ecoremedy had no problem handling the mixture and there were no adverse effects.

Other fuels were added to the gasifier as well, including spilled or spoiled feed and shredded documents, none of which negatively affected the steam production.

In fact, during the test 85 tons of high-quality ash were generated at a value of $250 to $325 per ton. “The ash coming from a system was very inert — meaning no pathogens,” says Walker. “It worked very well for that.”

And although Walker says there was some tweaking to the machinery at the very start, the Ecoremedy worked exceedingly well in turning litter to steam and creating a high-quality ash.

Next step — mortalities

The next phase of the project — testing to see if the system can incinerate animal tissue efficiently and cleanly, while creating steam and ash — is in progress now.

“Part of our vision is for this system to be portable,” says Walker. “If someone had a hog house burn or a poultry house fire, the incinerator could be pulled on site during the catastrophic events to get rid of mortalities,” says Walker.

“We’ve spent this summer getting it ready to be truly portable, in that we put a diesel-powered generator on a trailer and a carcass grinder on a trailer, each of which is on a bumper hitched trailer,” he adds. “Now all three units, the generator, the mortality grinder and the gasifier are truly portable, and can be pulled to any site for mortality disposal.”

The incinerating system is currently set up at an approved EPA compost site – for a 200-hog-per-day harvest facility. During the month of October the system was being tested to be sure it works and that all the components parts are compatible. Official testing will begin as soon as the Illinois EPA provides permitting approval.

Because animal tissue, versus litter, is being burned, the Ecoremedy system requires supplemental heat. In this case, propane is used, in large part because it’s portable. “Not everyone will have natural gas on site and diesel fuel doesn’t burn hot enough or clean enough,” says Walker.

Future of the system

Down the road, Walker and others would like to see renderers using the system. Cattle that are too old (over 30 months) to be processed for meat or bone meal could be incinerated and the heat captured for steam for use in rendering or to produce electricity.

“Basically, renderers could capture their costs back as energy and pay for the system,” says Walker. “It has tremendous potential for this whole BSE issue. I would like to see more companies, in both the U.S. and Canada, interested in this system’s value.”

For poultry operations, a permanent incinerator could be set up. They could burn through the litter routinely and burn mortalities when necessary.

“Ultimately, producers would use that steam from the incinerator to drive a turbine to make electricity and use it on-farm and/or put it in the grid,” says Walker. “That’s the next step and it will require some propane when disposing of the mortalities. But then the operator should get electrical costs back to pay for the propane use and it would be a recyclable green energy — a renewable green energy.”

Until then, what is for certain is that Ecoremedy is creating new options for farmers and how they handle their poultry litter and mortalities.