Faced with time-consuming drives to apply its manure and new phosphorus

management regulations, the Grenier family hog operation recently

turned to technology company Envirogain and its system of converting

manure into organic fertilizer.

Faced with time-consuming drives to apply its manure and new phosphorus

management regulations, the Grenier family hog operation recently turned to technology company Envirogain and its system of converting manure into organic fertilizer.

In the Canadian province of Quebec, which has a major hog industry, the manure problem has become so severe that a moratorium has been placed on the expansion of pig farms. In regions which have been found to have too much phosphorus in the soil because of manure application, pork producers have been forced to find other areas—often more than 50 kilometres from their breeding sites—to spread pig manure.

In addition, agricultural regulations spelled out by the Quebec Environment Ministry call for new phosphorus management rules to come into effect in three steps, in the years 2005, 2008 and 2010. Actually, phosphorus application is in excess compared to crop needs. Prior to 2010, the requirements call for a progressive reduction of phosphorus rate application in order to reach a balance with crop needs.

While the challenge to meet these requirements is great, help is coming thanks to a new hog manure treatment system that is being developed, marketed and operated by Envirogain, a technology firm in Saint Romuald, on the south shore of Quebec City. After five years of research on an experimental site, the firm is marketing a technology that will allow hog operations to continue production, and not have to be concerned about looking for new land to spread manure.

In 2000, Envirogain’s founders discovered that a French company, Dénitral, was working on a process similar to what it was aiming for. Envirogain developed a technical partnership with Dénitral to accelerate the development of its own technology for the Canadian market. Envirogain adapted the technology, sporting the Biofertile brand name, to the harsh realities of Quebec’s Nordic climates, and especially to the environmental requirements of the province’s Environment Ministry.

Company executives would now like to see their technology become a broader solution to the manure problems faced by pork producers in Quebec, elsewhere in Canada and in all areas with surplus liquid manure. “We hope that our technology can be used in all agricultural enterprises,” says Jocelyn Douhéret, an agronomist and director of market development at Envirogain.

The Envirogain process consists of transforming liquid manure into an odorless, clear and cleansed liquid containing just one percent of the initial phosphorus, and into an organic fertilizer called BOB (Biofertile Organic Base).

BOB, which is almost odorless, concentrates nutrients into a solid that represents only 15 percent of the initial volume of liquid manure.

The organic fertilizer can be transported long distances economically and be used to fertilize land elsewhere. “There is no other commercial technology of this type in Quebec or in Canada,” says Douhéret.

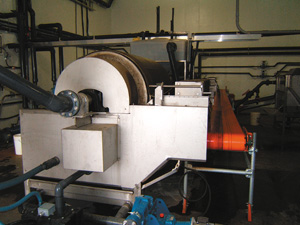

An aerobic bioreactor on the Grenier family hog operation, part of the Envirogain process. The process, an “activated sludge” type, is inspired from the classic concept used by wastewater treatment plants. An aerobic bioreactor on the Grenier family hog operation, part of the Envirogain process. The process, an “activated sludge” type, is inspired from the classic concept used by wastewater treatment plants. |

However, before Biofertile became operational and ready to be marketed, a research and development phase was necessary. It took place on a small school farm in Saint-Anselme, about 50 kilometres south of Quebec City. Research was conducted with the support of private investors and organizations such as the National Research Council of Canada (NRC), Economic Development Canada (with the TEAM program of the Ministry of Natural Resources) and the Centre québécois de valorisation des biotechnologies.

It’s now five years later, and the results were extremely positive, leading to Quebec’s Ministries of Agriculture and Environment authorizing the first commercial pig manure installation last year. The first Biofertile system was installed on the Grenier family farms in Ange-Gardien, about 65 kilometres southeast of Montreal, a grouping of five farms belonging to the same family.

Physically, the system looks like a wastewater treatment plant. Operational since January 2005, it includes a machine room, an adjacent big pit containing the bioreactor, a receiving gallery to store solid organic fertilizer and a lagoon for purified liquid which ends up being applied on neighboring lands.

The process, an “activated sludge” type, is inspired from the classic concept used by wastewater treatment plants in municipalities or by the pulp and paper industry. Envirogain’s experts adapted the process to the agricultural sector.

“The farms can treat 82 cubic metres of manure a day, the equivalent of the annual production of 55,000 pigs,” Douhéret says. “The treatment system is designed to manage 100 cubic metres a day.”

The Grenier farms, belonging to Rhéal, Jocelyn, Luc and Patrice Grenier— the third generation of farmers in the family—own 45,000 pigs and 900 breed sows. The pigs produce 30,000 cubic metres of manure, and Grenier farms only owns 200 hectares. Given the lack of available space for manure and because the Grenier farms are located in the Montérégie, a zone identified by the Environment Ministry as having a surplus of phosphorus, the farmers did not have too many options.

Making the situation even more urgent, the upcoming phosphorus control standards from the Environment Ministry would require the Greniers to have 1,000 hectares to spread the amount of phosphorus produced by the farm. The Grenier Farms use two tanks for the application of manure on fields, one tank from Houle and the second tank from DM Machinery. The problem is they, of course, have only 200 hectares.

Rhéal Grenier of the Grenier farms. “Other companies came to us with proposals but we chose Envirogain because its team solved our problems of manure treatment.” Rhéal Grenier of the Grenier farms. “Other companies came to us with proposals but we chose Envirogain because its team solved our problems of manure treatment.” |

“We had a big problem,” says Rhéal Grenier. “We had to spread 75 percent of our manure outside our land, on the land of other producers who used it as fertilizer. We had to transport our manure, then spread it ourselves. Not only does it takes time to transport and do the spreading, but other producers were in the same boat and were competing with us to find land to spread the manure.”

In other words, the Greniers had to reduce their phosphorus discharges, either by treating the manure, by reducing the number of hogs or by finding new land they could access. “We had a choice to make: Buy land, find other customers to spread our manure or buy and use equipment to handle the manure. As well, our pits for manure storage were out-of-date. The solution proposed by Envirogain came at the right time.

“Other companies came to us with proposals, but we chose Envirogain because its team solved our problems of manure treatment and took care of the solid residual materials.”

The project at the Grenier farms was made possible thanks to government help. The “Prime-Vert” program, financed by the Quebec Ministry of Agriculture, paid 50 percent of the system’s costs. Among other things, the program supports projects that reduce fertilizer volumes and decrease odor.

The Agriculture Ministry will pay up to $200,000 per farm. Since the Greniers operate five farms, they received a government grant of $1 million. They invested another $1 million themselves to build the treatment station, for a total cost of $2 million.

The Filtramat technology was developed by Dénitral, Envirogain’s technical partner. The process uses a tangential screen combined with a screw press to separate the liquid and the solids from the raw manure. The Filtramat technology was developed by Dénitral, Envirogain’s technical partner. The process uses a tangential screen combined with a screw press to separate the liquid and the solids from the raw manure. |

The investment allows them to reduce their manure management costs. Not only that, but their costs would have increased dramatically had they not gone ahead, because of the new Environment Ministry policies that are being implemented.

The aim of the system is to transform raw manure into a solid organic fertilizer by concentrating the nutrients contained in the manure along with purified water. The process removes phosphorus, nitrogen and the odors from the liquid part of the manure. At the same time, it reduces significantly greenhouse gas emissions as evaluated through the SMART report of the TEAM Program of Natural Resources Canada.

Using a 1.5 km long system of pipes, 50 percent of the manure from the Grenier farms is forwarded daily to the treatment station. The rest of the manure to be processed is transported by truck because the other buildings are situated too far away.

At ground level, the treatment station includes a room where the filtration machine sets are installed. A nearby electrical room contains computers and below it is the blower room. Ponds are built into the ground, below the filtration equipment. A 94-foot diameter aerobic bioreactor is installed outside, beside the station. On the other side is a 60-foot by 160-foot shed, constructed to store the solid fertilizer. Finally, a few metres away is the lagoon, containing the treated water, ready to be applied.

Throughout the system, a total of 15 ABS Group pumps, ranging in size from one horsepower to 10 horsepower, are used as part of the transfer process. The transported raw manure is moved to one pond built under the treatment station, which can receive up to seven days of manure production. The manure consists of mixed farrowing manure, finishing manure and nursery manure, so that a homogeneous mix—ready to be treated—can be obtained.

In the second step of the process, Filtramat is introduced. The Filtramat technology was also developed by Dénitral, Envirogain’s technical partner. The process uses a tangential screen combined with a screw press to separate the liquid and the solid from the raw manure.

The solid part, called primary solid, is forwarded by conveyor to the shed, adjacent to the filtration room, where it is stocked. This primary solid contains 45 to 55 percent water. “In fact, the primary solid is what the pig did not digest. Among other things, it consists of corn scales and cellulose,” says Patrick Ramsay, project manager for Envirogain.

Patrick Ramsay, project manager for Envirogain (left). “Buyers of the Patrick Ramsay, project manager for Envirogain (left). “Buyers of the fertilizer produced by the system come from more than 70 kilometres away,” says Ramsay. |

The liquid from the primary separation is forwarded to the bioreactor. “This is a nitrification phase by aerobic treatment, with air resulting from the blowers. It’s followed by a denitrification phase. So we change the ammoniacal nitrogen into athmospheric nitrogen and stabilized organic nitrogen. The rest of the organic load is digested by bacteria in the presence of oxygen, producing an activated sludge,” says Ramsay.

The manure treatment is done in a continuous process. Every day, a volume representing a thirtieth of the muds stemming from the bioreactor is forwarded to the Skimmat. This machine separates the treated water from the activated sludge, which becomes the secondary solids. It’s at this stage that primary solids and the secondary solids are mixed to give the organic fertilizer BOB 30 percent of dry matter with formula

3-6-2.

There looks to be no shortage of demand for the fertilizer. “Buyers of this fertilizer come from more than 70 kilometres away. They come at their own expense, at no charge to the Greniers,” says Ramsay.

The liquid resulting from the Skimmat is forwarded to the Flair, an innovative technology developed by Envirogain. “The liquid is sent by jets into a reservoir, containing plastic media that support bacteria in this additional process of biological purification. The Flair processes the liquid as well as the ambient air,” explains Ramsay.

The liquid treated by the Flair is then forwarded to the Polipur, another Envirogain innovation. The equipment possesses metal electrodes into which an electric current is driven. This makes the remaining solids flocculate (collect into lumps), which settle afterward. The result: liquid that passes by the Polipur will be cleared of some of the residual phosphorus and suspended materials.

The TheSkimmat separates the treated water from the activated sludge, which become secondary solids. Primary solids and secondary solids are mixed at this stage to give the organic fertilizer BOB 30 percent of dry matter with a 3-6-2 formula. |

This cleansed water is sent by pipes to the lagoon, where it’s stored. A geomembrane is placed in the bottom of the lagoon. This cleansed water is then ready to be applied to a 16-hectare area. “The lagoon has a storage capacity of 250 days, which respects the Quebec Environment Ministry specifications,” says Ramsay.

The station itself can last for many years. “The structure is entirely concrete, which doesn’t require much maintenance, and can last decades,” says Rhéal Grenier.

According to the manufacturer’s specifications, the roof of the structure has a life cycle of at least 15 years, the engines 12 years, the bioreactor 100 years, and the membrane of the lagoon 15 years, Ramsay says.

Once the system is in operation, the Envirogain-trained person in charge has to conduct daily tasks, such as equipment checks, that last 15 or 20 minutes. However, the station works without a full-time operator on site. The process is watched and controlled remotely by Envirogain, which creates a daily report and provides visits by a technical team every two weeks. Envirogain also offers an operations contract that provides assistance and maintenance.

The treatment station started working last May. Although manure produced in 2004 was spread on the fields of the Greniers’ customers, they should be able to put an end to that soon. “We hope that our manure from 2005 can be completely treated so that we do not need to spread it anymore,” says Rhéal Grenier.