While expanding his hog

operation, Iowa’s Dale Vincent took some proactive steps and was able

to take what was initially a negative situation involving attorneys and

turn it around by dealing directly with his neighbors—addressing their

concerns, including hog manure odors.

With the new barn complete, the Vincent Family—Colleen, Jason and Dale—had a ribbon cutting ceremony and open house for the new hog barn. More than 80 people turned out and were able to see how the Vincents are proactive in their farming methods, including manure management. With the new barn complete, the Vincent Family—Colleen, Jason and Dale—had a ribbon cutting ceremony and open house for the new hog barn. More than 80 people turned out and were able to see how the Vincents are proactive in their farming methods, including manure management. |

While expanding his hog operation, Iowa’s Dale Vincent took some proactive steps and was able to take what was initially a negative situation involving attorneys and turn it around by dealing directly with his neighbors—addressing their concerns, including hog manure odors.

What do all farmers dread? A call from a neighbor complaining about odors? Or worse, a call from a neighbor’s attorney? Or maybe it’s Iowa hog farmer Dale Vincent’s recent experience—a call from the neighbor’s attorney to stop the building of a new barn.

Dale, who already had a 4,000-head nursery, decided in 2005 to build a 2,400-head finishing barn. It was an opportunity for his son Jason, who had recently received his degree in swine production, to come back to the family farm. But while he was getting the required permits, one of his neighbors found out—and panicked.

The neighbor’s wife got on the Internet and started looking up all sorts of negative things against hog facilities, like odors and how the value of their home would go down, says Dale.

The neighbors hired an attorney to stop the building. Dale had to get an attorney through the Coalition to Support Iowa’s Farmers to respond. It wasn’t until the neighbors started getting bills and were seeing no progress (the Vincents were following all the rules) that they decided against attorneys, and talked face-to-face.

When Dale and his son Jason sat down with the neighbor, that’s when progress was made and solutions were found. “Basically I just listened to what he had to say,” says Dale “Many of his concerns weren’t based on good swine analysis or management and I was able to counter them,” says Dale.

For example, the neighbors had read that low levels of hog odors could affect a child’s overall health. Not only did Dale explain that his grown children were never affected, but that he had taken part in a health study approximately 10 years ago. “A nurse checked my lung capacity and took a blood sample. They did it again five years later. And my overall health had not changed.”

The neighbors were also concerned about more buildings on the property. “I explained how important it was to get buildings in the right place—away from water streams, and have driveways that do not go through a ditch or waterway. That’s why we built back from the road. And there wasn’t another site where we would want to build another building.”

The new 2,400-head finishing barn (above) features an eight-foot pit. “Having the manure stored under the barn, versus an outside pit, helps control odor,” notes Dale Vincent. The new 2,400-head finishing barn (above) features an eight-foot pit. “Having the manure stored under the barn, versus an outside pit, helps control odor,” notes Dale Vincent. |

And, of course, spreading manure was also an issue. “His first reaction to spreading was that he didn’t want any put on [near him],” says Dale. “I told him that we put it on every other year, and I would give him one week’s advance notice.” It wasn’t nearly as much as what the neighbor thought—in fact, the neighbor suggested he could send his wife and daughter Christmas shopping during the application. They wrote it up and recorded their agreement with the county.

The whole experience made Dale more sensitive to his neighbor’s feelings. “I started to become pro-active as to what I could do on my side of it,” he says. “I went around and talked to all the neighbors. I got good at listening to what they had to say. And when I informed them about what we were doing and how we were bringing my son back into the operation, they were very positive.”

Because Dale’s neighbors aren’t farmers, meeting them gave him a chance to relate to them. “I could show them what we have in common—like I coach youth baseball and am active in the Lions Club. That broke down a lot of those barriers.”

Dale also got to hear what was upsetting his neighbors. One wanted to know how the Vincents disposed of their mortalities. An area hog farmer threw his pigs out the back door and a dog dragged the decomposing pig into a neighbor’s yard. “That would be pretty negative to me too,” says Dale. “But it gave me an opportunity to tell them what we’re going to do when we have dead animals. I talked to them about how we use a compost building. We turned it into a positive.”

When the barn was complete, the Vincents had a ribbon cutting ceremony and open house for the neighbors as well as everyone who had worked on the project.

“We have so many negatives about pig farms in the press, that when people drive by a building and smell, they create instant connotations,” says Dale. “I wanted them to see what it was like on the inside of one of those buildings, and how modern they are.” And neighbors could also see how local businesses were a part of the project.

About eighty people came—quite a turnout on a day there was a big football game in town. They got to see first hand that the Vincents were as pro-active in their farming methods as they are in being good neighbors.

The nursery, 96 feet by 152 feet, was built in 1997. Its four rooms each hold 1,000 pigs. In the center is a walkway and an office. “I have windows in the doors, and have a lot of visitors come look in my nursery. It’s really enhanced it.”

There is a two-foot pit in each room and a pull plug system is used to remove waste on a seven-week cycle. The manure flows out to a 90-foot by 90-foot, 10-foot deep concrete storage tank with a 12-month capacity.

Around the nursery, the Vincents have planted at least 40 evergreen trees. They have also planted grass and put plastic (covered with rock) under the eves to keep erosion down. There are even flowerpots on the bulk bins in the summer. “We make it look like a showplace. We want it to show that we are proud to be pork producers,” says Dale.

They have taken equal care with the new 402-foot by 51-foot, wean-to-finish barn. In the center is an office, washer and dryer—a controlled environment away from the pigs—with 1,200-head capacity on each side. Under the building is an eight-foot pit. “Having the manure stored under the barn, versus an outside pit, helps control odor,” says Dale.

When the concrete for the pit was initially poured, Dale took an extra step to keep down odors. “We found out that manure samples from new facilities had a high pH. And when the pH is high, so is the odor level,” he says. “I talked to people who built buildings in the last four or five years and they all said that the first year seemed to be the worst odor, but no one knew why.”

After some research Dale discovered the pH levels were caused by the chalky substance found on the surface of new concrete. When water dissolved it, the pH level rose. To avoid this situation, the Vincents swept the pit out and had the walls, beams, pillars and floor sprayed with a product similar to muriatic acid. An eastern Iowa company, Sprinkle Wash, sprayed a product called Acid Wash on these areas. “Muriatic acid doesn’t always have the same potency. And this product had an added detergent so it would adhere to the concrete better,” says Dale. It worked.

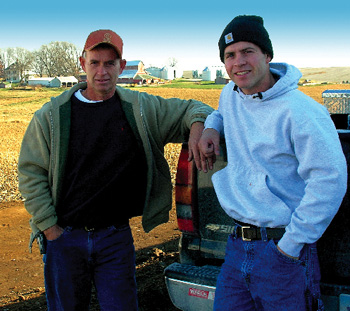

When Dale and Jason Vincent (above) sat down with a neighbor concerned about how manure would be managed with the new barn, that’s when progress was made and solutions were found. The solutions included giving the neighbor advance notice of manure being spread on the farm. When Dale and Jason Vincent (above) sat down with a neighbor concerned about how manure would be managed with the new barn, that’s when progress was made and solutions were found. The solutions included giving the neighbor advance notice of manure being spread on the farm. |

Dale and Jason also added six inches of water in the first pit before the pigs were brought in. “That gave us a base, and allowed the first manure to start breaking down. Once the pigs were there a month, we put in an additive to help break down the manure quicker. The only other additive we used was to break up the crust that builds on the top.” This additive was Accelerator Plus from Agtech Products Inc.

In the fall, the Vincents hire Gilbert Troyer and his company, Iowa Grow, which uses a dragline system to inject the manure from the pits into fields. Using the manure as fertilizer the past 15 years, he’s saved a considerable amount of money. “The energy costs, and the costs of commercial fertilizer and diesel are a lot higher than they used to be. Now there’s a lot of interest in hog manure. The value of the manure is so much greater than it was even three or four years ago,” says Dale.

Lastly, to help ensure there is as little odor as possible, Dale, his wife Colleen and Jason recently planted 350 trees, creating a green belt 450 feet across. The trees will not only catch dust and wind and diffuse odors, they will also block the neighbor’s view of the barn from his back yard.

Dale feels the entire experience—although initially negative—has been a good one.

Besides the better neighbor relationships, there have been other positive experiences. Jason was recently in a Coalition ad aimed at drawing young people to agriculture. And at a Coalition seminar, Dale was on a panel with two other producers in Iowa that had conflicts with neighbors. “It was probably one of the hits of the day because it gave people an idea of the mistakes that we made,” says Dale.

If he had it to do all over again, he would have talked to his neighbors sooner. “At the time, I didn’t even know if I was going to meet the rules to get the permit. I didn’t go talk to my neighbors because I didn’t want to stir the waters.

“Now I tell people, ‘Go talk to them; tell them what you’re going to do and the reason why. And get an understanding of where they are coming from.’ The worst thing a farmer could do is actually move dirt with the neighbors not knowing what you’re doing.”