Features

Compost

Considering windrow composting

A Wisconsin study looks at improving water quality through windrow composting.

September 24, 2019 by Diane Mettler

Outdoor windrows at Farm B are piled together in this shape to maintain good

conditions for composting.

Outdoor windrows at Farm B are piled together in this shape to maintain good

conditions for composting. Farmers are continually looking for ways to control runoff from their operations. A new study demonstrates that composting may be a valuable tool.

Dr. Laura Good, a soil scientist in the department of soil science at the University Wisconsin-Madison, and Pamela Porter, research program manager at the university’s Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems, were tasked with analyzing three dairy farms in Dane County, WI, that were composting bedded pack manures to determine the impact of windrow composting on the Yahara River Watershed.

Bedded pack manures come from livestock housing where cornstalks, straw, wood shavings, and/or sand are spread on the floor for bedding. This solid manure from young and dry cows – typically managed separately from the manure produced by lactating dairy cows – can make up 20 to 25 percent of a dairy farm’s total manure production.

Over two years, Good and Porter studied the three operations to evaluate potential phosphorus (P) runoff losses on these farms following compost application to cropped fields, and compared them to expected losses from applying the manures directly to the fields without composting. Their secondary objective was to document the agronomic benefits and costs associated with composting and to evaluate the costs per pound of P runoff reduction.

Farm A

To control moisture over the winter, Farm A built a covered storage area where manure from 400 mixed age heifers was composted year-round under a roof. The windrows were 250 feet long, 15 to 20 feet at the base, and six feet high.

The annual raw manure production was approximately 3,300 tons, plus 220 tons of corn stalks, straw, and other organic materials. The windrows were constructed by combining manure and bedding cleaned from different buildings with wetter and drier manures. Over the two years, the farm used various off-farm materials (corncobs, sawdust and sand) in their bedding.

“The nutrient analysis of the finished compost has varied somewhat over the course of the project,” Good says. “For our comparison, we used an analysis from the fall of 2017 that contained some ground corncobs and comparatively little sand.”

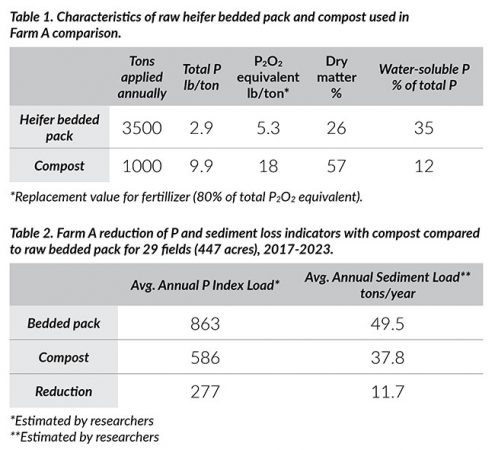

Farm A results

The result of composting decreased the volume of the manure and the potential for the P in the manure to dissolve into water. With respect to the phosphorus reductions, Good and Porter created a model and estimated the farm could reduce P and sediment running off their fields and entering waterways by applying compost instead of raw manure over a seven-year crop rotation.

Farm B

The second farm also composted year-round, but the windrows were outdoors. The manure came from 200 steers and 25 cows located several miles from the home dairy farm. Cornstalks, straw and sand were used as bedding.

On a weekly basis, 90 tons of bedding and manure was removed and 40 tons of new sand was added. Good noted in her analysis that the bedded pack was approximately 40 percent sand and that variations in sand content in the compost lead to variations in nutrient contents by weight.

The results also indicated a small tonnage reduction due to the outdoor windrows, which gain moisture from rain. The outdoor composting also resulted in some loss of phosphorus, nitrogen and other nutrients, although some nitrogen is always lost in composting – even under a roof, according to Good. Nonetheless, phosphorus requirements were met by the phosphorus in the manure and compost applications when fertilizing the fields. Putting the manure in windrows for composting allowed the farm to avoid spreading raw manure in the winter, when runoff risks from snowmelt and rain on frozen soil are high compared to the rest of the year.

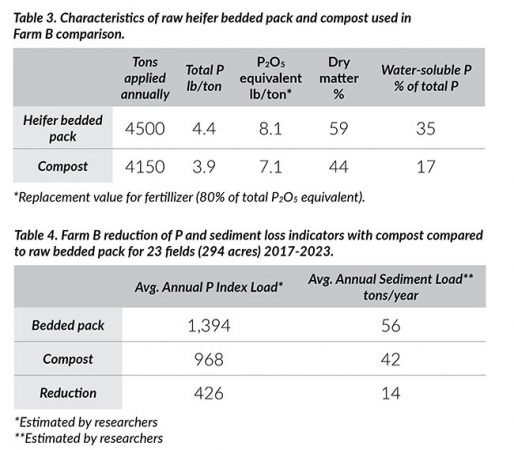

Farm B results

The use of compost cut the expected average phosphorus runoff losses across the crop rotation by about a third, even though the starting losses were higher, due to steeper fields with more erosion and higher per-acre phosphorus application rates.

It is likely, however, because of the outdoor windrows, that the area beneath the windrow has a high concentration of phosphorus and other nutrients. In addition, windrows should be carefully located to avoid areas with risk of surface runoff or leaching to groundwater. Therefore, finding areas suitable for windrow placement is an important consideration when contemplating outdoor windrow composting.

Farm C

Farm C composted seasonally. The farm created windrow compost from approximately 65 calves and 25 cows in the summer and composted until the crops were off in the fall. The farm spread 1,200 pounds of sand per month in heifer pens with cornstalks and/or straw added for bedding over the sand.

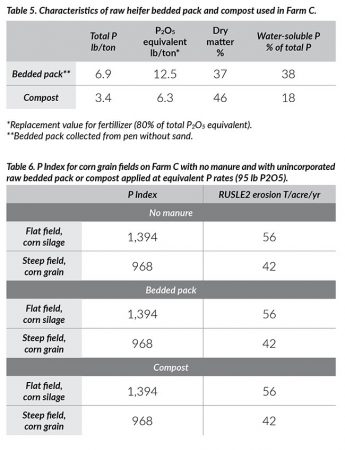

The compost was applied to a 13-acre field outside of the watershed being studied, and in places where there were steep inclines. The flat and steep slope comparisons shown in Table 6 were examples of typical fields on the farm that Good used to determine how they might compare to raw manure on the farm itself.

Farm C results

Both manure and compost reduced estimated erosion compared to an un-manured field, but the compost was more effective. And, despite some fields having steep slopes, the results were positive.

“Composting was positive across the system for reducing phosphorus losses due to runoff.”

“Composting was positive across the system for reducing phosphorus losses due to runoff,” Good says. “In some fields in some years, you might make a tradeoff that it would make a little bit more phosphorus loss because you’ve moved the applications to a different crop or timing. But overall, farm-system wide, it was very helpful.”

Additional benefits

Good says the results show the definite advantages to composting. “Anytime you have more of the rain or snow melt that runs off rather than leaches in, it’s riskier for runoff,” says Good. “So, if you have a system that helps you avoid having to apply the manure at a time when it’s really risky for runoff, that’s one big benefit. That was a really big benefit here, in addition to the flexibility of when and where you can apply it and what crops you can apply compost to compared to raw manure.”

“So, if you have a system that helps you avoid having to apply the manure at a time when it’s really risky for runoff, that’s one big benefit.”

She added that in the end, composting didn’t reduce the amount of phosphorus that was in the manure, but it did reduce the water solubility of that phosphorus.

The famers in all three farms cited other advantages to windrow composting as well:

- The compost manure can be applied to growing alfalfa when it’s needed most, without damaging the crop.

- Manure pathogens are reduced during the process and the compost contained higher concentration of nutrients and less moisture.

- More flexibility when applying to fields, or even selling the compost to other farms.

- Compost used as bedding cut costs.

- Using compost on the fields also lowered fertilizing costs because there is no need to purchase additional P fertilizer.

- Capital outlay for a composting facility is less than a manure storage tank.

- One farmer saw a yield increase in alfalfa of 10 percent using compost.

The next step

Because of the heat that is generated during the composting process, the windrows need to be turned weekly, allowing oxygen to be added to the pile and waste gasses to vent, which, in turn, accelerates the composting process. For the analysis, the three farms rented a compost turner owned by a company that circulates it throughout Wisconsin.

Jeff Endres, owner of Farm A, decided to build his own. “I needed a turner that would complement my space,” he says. “I had an idea in my mind about what I wanted to do. I worked with a local engineer at a manufacturer, and we built [the turner] from scratch. It fits on the back, on the three-point of a tractor,” he explains. “You back into the windrow very slowly and the beater kicks the compost onto the cross conveyor. And then it restacks it to the side.

“Our primary carbon source is corn stover or corn stalks. So, the beater has aggressive teeth on it that actually help scythe the material and rip it apart. These aggressive teeth really help break down the carbon and actually, speed up the composting process,” Endres adds. “I come up with the carbon to nitrogen ratio that’s considered finished compost on my compost in eight to 10 weeks.”

Endres today composts roughly 2,500 tons of material per year, and 700 yards of raw material creates about 300 yards of compost. The compost is primarily used on the farm’s alfalfa field, and because he is spreading his own manure product on to the hay ground (versus using commercial fertilizer), he says the farm’s efficiency has increased substantially.

Taking composting to the community

As a member of Yahara Pride Farms, a farmer-led conservation group that promotes soil health, Endres is taking the composting concept even further.

“We’re working close with the county and our local sewer district in an adaptive management program,” Endres says. “I’ve got 10 windrows on 10 different farms that we basically put out in the fields in the winter months, with the idea of not spreading it and reducing the runoff. We then return to the windrows and turn the manure into compost during the summer months. Because my turner is mobile, I can pick it up and run down the road with it with a tractor and go from job to job.”

Yahara Pride Farms is studying the economics of composting while monitoring the water quality. They track the results of the 10 different compost windrows and how they respond. “Most of the time if we have issues, they are either too wet, or they’re too low in carbon,” Endres says. “We’re also trying to see if we can concentrate this manure enough that we can move it further, so farmers who don’t need the nutrients on their farm could potentially sell it to somebody who does.”

After working with composting over the past few years, Endres is satisfied with the product. “It has pretty good phosphorus levels,” he said. “Our average analysis per ton is about 15 nitrogen, 13 to 14 on phosphorus, and about 30 on potassium. I like the flexibility of being able to spread manure at the time of the year you need it the most on growing crops. I also do like the that I’m getting a little bit of a yield bump, I feel, on my 350 to 400 acres of alfalfa.”

Both Good and Endres are looking forward to seeing more farmers applying the information available on windrow composting and experiencing positive results.