Features

Applications

Poultry

Chickens dieting to help Delaware’s waterways

April 11, 2008 by Tracey Bryant

Dieting to lose weight and improve your health?

Millions of chickens in Delaware – one of the top US poultry producers – have been on a diet to reduce their impact on the environment and improve the health of the state’s waterways, and it appears to be working.

|

| University of Delaware researchers formulated various phytase-modified diets for the study which involving thousands of broiler chickens. The birds were examined for bone health and growth, as well as the phosphorus content of their manure, beginning as chicks up to market-size birds. |

Extensive research led by Dr. William Saylor, professor of animal and food sciences at the University of Delaware, has confirmed that Delaware chickens now digest more of the phosphorus, an essential nutrient, in their feed, thanks to the addition of a natural enzyme called phytase. As a result, about 23 percent less phosphorus is output in chicken manure.

So now when poultry litter is used to fertilize a farm field, a lot less phosphorus is available to potentially be carried off in storm water to a river or bay.

And that’s good news for waterways like Delaware’s Inland Bays, where overloads of nutrients, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, have contributed to serious water quality problems, such as massive blooms of algae and fish kills.

To put it in perspective, in 2006, Delaware farmers produced more than 269 million broiler chickens – 1.8 billion pounds of poultry – valued at more than $739 million, according to the Delmarva Poultry Industry. Those chickens produced more than 280,000 tons of waste.

According to recent analyses by Dr. David Hansen, University of Delaware assistant professor of soil and environmental quality, there are now about 19 pounds of phosphorus in a ton of Delaware poultry litter compared to 25 to 30 pounds of phosphorus per ton of litter just five years ago. The 30 to 40 percent reduction is credited to phytase-modified diets and other nutrient management practices being adopted by poultry farmers under Delaware’s Nutrient Management Law of 1999. That reduction means the phosphorus load to the environment has been reduced by some two million to three million pounds per year.

|

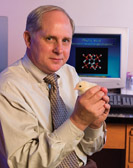

| Extensive research led by Dr. William Saylor, University of Delaware professor of animal and food sciences, has confirmed that Delaware chickens now digest more of the phosphorus, an essential nutrient, in their feed, thanks to the addition of a natural enzyme called phytase. Photo By Kathy F. Atkinson. |

Addressing a weighty problem

“Phosphorus is essential to all life,” says Dr. Saylor. “Livestock, particularly poultry and swine, are fed a diet of seeds and grains. However, two-thirds of the phosphorus in this food is phytic acid or phytate, which is a form of phosphorus that poultry and pigs can’t digest, so it goes right through them,” he notes.

“Phytase is an enzyme that is added to poultry feed at the mill that helps broilers and other poultry utilize more indigestible phosphorus,” says Dr. Saylor.

Over the past several years, Dr. Saylor and colleague Dr. J. Thomas Sims, the Thomas A. Baker, Professor of Plant and Soil Sciences and associate dean of the University of Delaware’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, have led a team of experts in analyzing the nutritional requirements of poultry and swine and the effects of phytase-modified diets on the livestock and the environment as part of a ‘feed-to-field’ approach to nutrient management. The research was funded by an $821,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Initiatives for Future Agriculture and Food Systems.

The scientific team included poultry nutritionists Dr. Roselina Angel from the University of Maryland and Dr. Todd Applegate from Purdue University; plus Dr. Wendy Powers, a swine nutritionist, formerly at Iowa State University and now at Michigan State University.

At the University of Delaware, Dr. Saylor and his students formulated various phytase-modified diets for a series of studies involving thousands of broiler chickens. The birds were examined for bone health and growth, as well as the phosphorus content of their manure, beginning as chicks up to market-size birds.

The painstaking research defined the boundary at which the total phosphorus levels in a broiler chicken’s corn-soybean meal diet can be reduced without detriment to the birds’ health, as well as the percentage of phytase that can be added to the feed to allow the birds to digest more phosphorus, leaving less to literally ‘go to waste’.

The data have been shared with a nutrient management partnership involving the poultry industry, environmental regulators and the academic community.

Phytase at ‘nucleus’ of nutrient management

Millions of chickens in Delaware have been on a diet to reduce their impact on the environment and improve the health of the state’s waterways.

|

| Research at the University of Delaware has confirmed that Delaware chickens digest more of the phosphorus in their feed with the addition of phytase. As a result, about 23 percent less phosphorus is output in chicken manure. |

“It certainly factors into our decision-making process,” says Dr. Ted Miller, director of nutrition and research at Mountaire Farms Inc., in Selbyville, of the University of Delaware’s phytase research.

The company has 600 growers across the Eastern Shore, who produce 150 million broiler chickens a year.

Dr. Miller serves on an advisory committee in the University of Delaware’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources and meets regularly with Delaware and Maryland scientists as an industry co-operator.

“Phytase has been at the nucleus of industry co-operation and regulations to deal with nutrients,” says William Rohrer Jr., administrator of the Delaware Nutrient Management Program. “It has significantly reduced the phosphorus going into our waterways.

“The university’s phytase research has provided two critical things,” Rohrer notes. “It’s brought the science to the table and helped industry take advantage of the enzyme. It’s also helped us to quantify the reduction of phosphorus to the environment.”

William Vanderwende, chairperson of the state’s Nutrient Management Commission, says he has been contacted by several states that want to model their nutrient management program after Delaware’s. While he does not raise poultry, Vanderwende operates a dairy farm near Bridgeville, with 700 dairy cows and 3000 acres of crops. “All in all, these phytase diets are doing the job,” Vanderwende says. “And I know these scientists are working to see if they can get the phosphorus numbers even lower.”

|

| Dr. Saylor’s research shows the boundary at which the total phosphorus levels in a broiler chicken’s corn-soybean meal diet can be reduced without detriment to the birds’ health, as well as the percentage of phytase that can be added to the feed to allow the birds to digest more phosphorus, leaving less to go to waste. |

Dr. Saylor has been interested in animal nutrition since he was a boy growing up in Butler County, Pennsylvania. He “always had animals,” including rabbits, sheep and chickens. After high school, he headed to Penn State, where he received his bachelor’s degree in dairy science, master’s degree in animal nutrition and then a doctorate in poultry nutrition. “There are a lot of good people working in poultry to address the phosphorus issue,” Dr. Saylor says. “Our poultry industry in Delaware is basically surrounded by water, and because of its size and concentration, environmental issues are of great concern,” he says.

“Phytase is definitely a positive piece of the water quality puzzle,” says John Schneider, manager of the Watershed Assessment Section in the Division of Water Resources at the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. “We are seeing less phosphorus in water samples from all over the state,” Schneider notes. “Clearly, we’re doing a lot of things right.” -end-