With

an increasing herd size, New York’s Fessenden Dairy was looking for a

more effective way of handling its manure and opted for the On Farm

Fertilization Recovery System or OFFRS, a nutrient management system

that goes well beyond the traditional collect and spread method of

manure handling.

With an increasing herd size, New York’s Fessenden Dairy was looking for a more effective way of handling its manure and opted for the On Farm Fertilization Recovery System or OFFRS, a nutrient management system that goes well beyond the traditional collect and spread method of manure handling.

For New York dairyman Tim Fessenden, one of the most rewarding moments in confirming that they were indeed on the right path in terms of handling their manure came shortly after they set up their composting system. Some neighbors had voiced concerns in the past about the farm’s manure management system and odors. “The same people who had been voicing these concerns about our manure management were now among the first to pull into the barn yard with their pick-up truck and $20, asking for a load of compost,” says Fessenden. “To me, it showed what we have been able to accomplish. With the new system in place, we were able to turn things around 180 degrees.”

One of the first things the Fessenden Dairy did in setting up the compost business was to develop a brand name—Tender Loving Compost —and trademark it. One of the first things the Fessenden Dairy did in setting up the compost business was to develop a brand name—Tender Loving Compost —and trademark it. |

Like all livestock farm operations, the whole area of manure management at the dairy has taken on a higher priority in recent years, notes Fessenden. He has been working on the farm since 1976 and now operates the dairy, having purchased it from his father. “It used to be the case that we didn’t talk about manure much at all,” he says. “Now it seems like anytime two dairy farmers get together, manure management is all that they talk about.”

The Fessenden dairy farm, having been in the family for five generations, has evolved with time, as has its size and manure management system.

Up until the mid-1980s, most farms in this area of upper New York State were 60 to 80 cows, and a large farm would be 100 cows. The Fessenden farm took a big step when it went from a diversified operation—with cash crops, cattle and dairy—to focusing on dairy with their Holstein cows.

“In 1989, we increased the herd size from 120 cows to 250 cows and devoted our acreage towards forage production and our efforts towards milk production.” About 500 acres of corn are grown each year, in addition to 700 acres of alfalfa.

Further well-planned expansions followed, to the point where the farm now has 650 milking and dry cows, and 580 heifers and calves. The latest expansion came in April 2004, with a remodeling of the milking parlor and 100 additional cows.

This resulted, of course, in having to deal with more manure and the odor associated with larger quantities of manure. As an interim measure, they went to a satellite storage facility. But Fessenden, following in the family tradition, was looking for a more sustainable, and long-term, solution.

“The farm has typically been progressive in terms of reacting to the concerns of our neighbors,” he notes.

They started looking around at how manure was being handled, not only in their area, but in the US, and even around the world. And if they ended up going with a slightly different method, that was fine with Fessenden. “I wasn’t going to accept the fact that you put all the manure in a hole in the ground and take it all out when you want to, and offend the community along the way. I did not want to go in that direction.”

The Fessenden farm handles over 16,000 gallons of manure per day and their top priority is to return the nutrients from that manure back to the soil.

The new direction in manure management for the farm came from Syracuse University professor Richard McClimans. As Fessenden terms it, McClimans, a professor in the School of Environmental Science and Forestry, turned them on to different ways of handling the manure that would be beneficial for the farm, the community and the crops, all at once.

The FAN drum dryer (top) receives manure solids exiting overhead from a series of press screw separators and a centrifugal separator. Separated manure solids exit the dryer drum unit (bottom) and are deposited into one of two collection piles. The FAN drum dryer (top) receives manure solids exiting overhead from a series of press screw separators and a centrifugal separator. Separated manure solids exit the dryer drum unit (bottom) and are deposited into one of two collection piles. |

The system: On Farm Fertilization Recovery System or OFFRS. It involves a number of different elements and essentially combines the practices of solid waste separation, thermophilic compost, vermicomposting, aeration and biofiltration to process both the solid and liquid parts of the slurried manure from their 650-cow herd. Besides McClimans, Brian Jerose, now a partner in WASTE NOT Resource Solutions and a research coordinator for Environmental Fertilization Corp, was also involved in the Fessenden project.

“It was unique in that it was made up of a number of components of manure handling that could work together, but they did not rely on each other,” explains Fessenden. “It involves putting some relatively simple components together in a method that could capture the benefits of all the components. But if for some reason, certain elements do not work well, the whole approach does not collapse.” It’s a nutrient management system that goes well beyond the traditional collect and spread method of manure handling, he notes.

The system begins, of course, in the barns, where slurried manure flows into a series of concrete tanks. The manure is agitated with Houle agi-pumps, solids are separated and Advanced Aeration units reduce the ammonium nitrogen levels and biological oxygen demand.

The manure is then pumped into four FAN separators. In unit one, the solids in the slurry are forced through a screen to reduce the solids content from 10 percent to five percent. In unit two, the screen size is finer and the solids content is reduced further, to 4.5 percent. Unit three is a FAN high-speed centrifugal separator that concentrates the remaining solids to then be fed to the final FAN press-screw separator. The manure solids from the FAN separators then fall on to a conveyor.

Manure solids fall from the conveyor into static aerated compost piles. Air is forced through channels and holes in the floor to provide oxygen to the decomposing materials.

The manure solids are left on the aerated floor for 30 days, reaching temperatures of 120 to 150 degrees F for 21 days or more. This thermophilic process kills all weed seeds and harmful pathogens, and some of the moisture is removed.

At this point, the farm has immature compost. As the material begins to cool, it is moved outside to windrows to finish the curing process.As the material begins to cool—atabout four to six weeks—it is moved outside to windows to finish the curing process. The windrows are turned weekly with a front-end loader to help the curing process. After three to four more months, the compost has become mature. The moisture, odor and harmful weeds seeds have all been reduced and the manure solids are ready to be used as composting mulch.

“It sounds like a pretty simple process, but the devil is in the details and that’s where our commitment to quality makes the difference,” says Fessenden. “We monitor temperatures daily when the piles are in the compost barn. And once the compost is placed outside in windrows, the temperatures are monitored weekly.”

The system has been fully operational since 2000, but Fessenden notes they have made numerous modifications since then. The latest came in 2004, when the herd size was increased. “But it’s the same basic principles. We’re trying to do as much as we can with solids separation at the front part of the system and that allows us to do more effective odor control of the remaining liquids, either through aeration or microbial manipulation.”

Fessenden characterizes the modifications as tweaking, rather than big changes. They started using press screw separators and have since moved on to using separators with more capacity, adding the high speed centrifugal

separator to help enhance the degree of separation.

The numbers tell the story: “Through solids separation, we’ve been able to achieve 66 percent solids recovery, which is really at the upper end of the scale. In doing that type of recovery, we achieve 38 percent phosphorus recovery and 35 percent potassium recovery.

“That’s the type of reduction in nutrient loading that we’ve been able to send out in the solids stream, all of which is used off farm.” Bernard Sheff, P Eng, of Sheff and Sons Engineering, helped to compile this data and fine tune the

system.

The most recent addition to the system came in December 2005 with a FAN compost drum dryer (CDD). This unit is used on the farm as a bedding recovery unit. The manure solids that pass through the CDD are dried to 45 percent dry matter and heated to 160 degrees F. This controls harmful pathogens, while creating a bedding source for the cows and utilizing the heat created from the microbial activity of the solids. The economics of the CDD look very favorable, but long-term results are pending, says Fessenden.

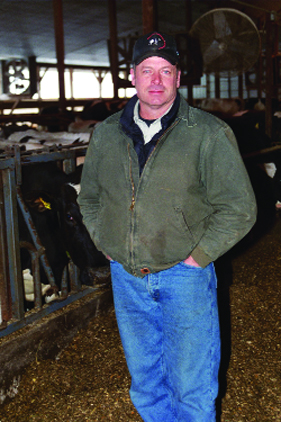

Tim Fessenden on the OFFRS system: “It was unique in that it was made up of a number of components of manure handling that could work together, but they did not rely on each other.” Tim Fessenden on the OFFRS system: “It was unique in that it was made up of a number of components of manure handling that could work together, but they did not rely on each other.”

|

Fessenden admits that marketing their compost was a challenge at first. But each year, sales have doubled, to the point that all of their compost is now used off farm. “It’s a matter of getting the product out there, doing a bit of advertising, making the connections and getting people interested,” he explains. “That part of it is something that maybe not every dairyman would choose to do. It can be quite time-consuming. There are days when you’d think that marketing compost is the only business that you are involved in.” That said, there is the constant reminder that it moves about 34 percent of their total volume of manure off the farm to customers who want the product. “To me that justifies the system right there.”

One of the first things they did in setting up the compost business was to develop a brand name—Tender Loving Compost—and trademark it. Any packaged compost goes out in a Tender Loving Compost bag, complete with the company logo of a very happy dairy cow.

Their largest compost customer is a retail outlet in the nearby town of Ithaca, which moves a lot of bulk and bagged material for them year round. The next largest customer buys material in bulk, mixes it with other material, and markets the product under its own name on the East Coast.

“We have five or six large customers that account for perhaps two-thirds of what we produce. The rest is a customer base of about 600, and that business seems to repeat every spring and fall.” They’ll deliver smaller quantities to these customers, who are mostly within a 40-mile radius of the farm.

They’ve made some adjustments to what they produce along the way. They used to have a vermi-composting operation as part of the overall system, enlisting an army of red wiggler worms in beds to produce premium compost. But Fessenden decided to let that component of the operation hit the dirt. “It was probably the highest quality compost available, but we found that consumers in the marketplace did not understand or appreciate the quality. We didn’t see a big enough opportunity there to keep producing it.

“But that wasn’t a big deal,” he adds. “That’s why this whole system works well. Just because the vermi-compost did not go doesn’t mean the system as a whole doesn’t work. It’s a matter of figuring out which components do work.”

A pile of manure solids on the collection floor that A pile of manure solids on the collection floor that funnels heated air through outlets in the concrete floor. |

The farm and compost operation is located in the small town of King Ferry in upper New York State. At one point, Fessenden notes, all their neighbors were farmers or somehow related to farms, and there was an understanding of the odors that sometimes come from a dairy operation. But the neighbors have changed over the years, and non-farm folks seem to have a lower tolerance for manure odors.

As noted at the start, these are the compost customers who really make Fessenden happy, the ones who head over with their pick-ups, ready to pay their $20 for a load of compost. “It’s a great turnaround and that is probably what I consider to be the biggest accomplishment of the system,” he says. “I guess we should be more focused on the economics, but if we have happy neighbors, I can keep farming.” That is not an insignificant point, considering there has been a Fessenden farming on this land since 1863.

And they’ll keep working away at things on the manure management side, notably on the liquids side. “We haven’t quite got a system for satisfactory odor control with the liquids. We’re going to try a different kind of aeration process to better control the odors.”

The intent is to be better able to irrigate the crops with odor-controlled liquids. “What it comes down to is people don’t want to smell manure. If we can keep the odor within reason, then I think we’re doing pretty well.”