Eastern manure management

practices are successfully meeting western manure management practices

at the Spring Grove Dairy in Wisconsin.

Eastern manure management practices are successfully meeting western manure management practices at the Spring Grove Dairy in Wisconsin.

East is meeting west at the Spring Grove Dairy in Brodhead, Wisconsin, as partners Dan and Mary Monson have adapted many of their animal and manure management practices from California.

“We’ve taken the management style they have in the West and tried to acclimate it to the Midwest,” says Dan Monson, who operates the facility with partners Cornell and Teri Kasbergen and Kara and George Kasbergen. “There are two things that are different at Spring Grove Dairy that you would typically not see in the Midwest. We sit on 80 acres, but we purchase all of our feed. Our forage is purchased with a manure spreading arrangement.

“Two, we have a water flushing system where we recycle the water. There are tending to be more of these in the Midwest, but there are still not that many because of the cold temperatures.”

Not only is the water recycled, sometimes several times before it’s used to flush the barns, but Monson also recycles manure solids into cow bedding material—another uncommon practice.

Monson credits spending five years in Tulare, California, as well as partners Cornell and Teri Kasbergen, who milk 3,200 cows in Tulare, and George and Kara Kasbergen, who milk 3,000 cows in central Illinois, for much of the Western management style.

Six times a day, operators flush the barns’ inside feeding lanes at Spring Grove Dairy, and three times a day they flush the outlying lanes. The practice uses about 450,000 gallons of recycled water. Six times a day, operators flush the barns’ inside feeding lanes at Spring Grove Dairy, and three times a day they flush the outlying lanes. The practice uses about 450,000 gallons of recycled water.

|

Built in 1998 and operational in 1999, Spring Grove Dairy comprises two 88-by-900-foot-long freestall barns with permits to house up to 1,800 head. Currently, Monson milks about 1,650 head.

Six times a day, operators flush the barns’ inside feeding lanes, and three times per day they flush the outlying lanes. The practice uses about 450,000 gallons of recycled water to which an additional 12,000 to 15,000 gallons of “fresh water” from washing the parlor and milking equipment are added.

But Monson is quick to point out that even the fresh water has been recycled as part of the dairy’s overall resource-management philosophy. For every gallon of milk produced, they use two gallons of water to do the initial cooling. After being used as a coolant, the water is stored in an old milk tank until it’s used to wash parlor floors or provide 60-degree drinking water for the cows. Then it’s used to flush the barns.

“We have to pay for every gallon that has to be hauled or pumped on someone else’s land in the form of manure water whereas in other parts of the county, a lot of wastewater is pumped by electrical pumps to irrigate land,” Monson says. “In our case, we are looking to minimize water use, even though we have a tremendous amount of water.”

From the barns, the manure slurry is gravity fed through a concrete-lined flume to the manure solids separator, after which leftover liquid is recycled.

Until last summer when the flume and separator were installed, Monson says a narrow series of drop structures leading to an underground pipe carried the slurry to the first of three clay-lined lagoons. Combined, they have a capacity to legally hold 25 million gallons.

Because the pipe discharged the liquid into the bottom of the lagoon, it created challenges to operate the system, especially in winter conditions.

Manure solids are recycled into cow bedding material at the Spring Grove Dairy. “The cows just love it,” says Dan Monson, who operates the dairy with several partners. Manure solids are recycled into cow bedding material at the Spring Grove Dairy. “The cows just love it,” says Dan Monson, who operates the dairy with several partners. |

The new system, which Monson designed, involves a sloping, wider flume system at the end of the barns. Now the only time there’s material in the system is during actual flushing. Tiry Engineering of Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, worked with Monson to ensure his design met Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources requirements. And Concrete Systems Inc of Browntown, Wisconsin, poured the concrete.

Heading into winter, Monson was concerned that colder temperatures might affect the new system, particularly the flow. But after several days of sub-zero temperatures, “everything is working great, so it did eliminate some of the original design challenges we had.”

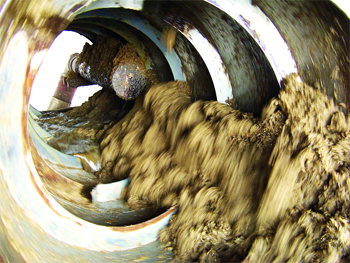

Monson added the IFRS 36 manure separator from Accent Manufacturing Inc in July 2005 to remove the solids and accompanying odors from the flush water, improve cow herd health and possibly create another revenue source. “The objective is to be as good a neighbor as we can,” Monson says.

He chose the Accent unit because of the company’s reputation for building separators for food processing waste that typically has a high water content.

“Because of our flush system, it creates a waste stream that is a very low solids, high water type of product,” Monson says. “Most separators are intended to work with liquid that is more than 10 percent solids. This equipment has stood the test and worked very well.”

Each day, between 22 and 23 tons of solids with about 75 percent moisture come off the Accent separator. Workers then put the solids in piles to let additional water leach back into the storage ponds. Each day, between 22 and 23 tons of solids with about 75 percent moisture come off the Accent separator. Workers then put the solids in piles to let additional water leach back into the storage ponds. |

Each day, between 22 and 23 tons of solids with about 75 percent moisture come off the separator. From there, workers put it in piles for at least two weeks to let additional water leach back into the storage ponds. The solid’s moisture content drops to about 60 to 65 percent.

When Monson was considering how to treat the solids last summer, he read several articles dealing with the subject for hot, arid areas. But he had little luck finding answers to his questions about practices for humid, temperate regions.

So he conducted experiments with three different treatments—windrows turned regularly with a front-end loader, windrows turned regularly with a mechanical compost turner and a static pile that was turned once.

Monson monitored temperatures within each treatment to ensure the material reached 130 degrees to kill pathogens. He also had a laboratory run tests on samples from each treatment to measure E. coli, Streptococcus and other detrimental gram-negative bacteria. Much to his surprise, the static pile appeared the best. “One stood out, and it’s the one I thought would be the worst,” Monson says. “With the big pile—consistently after three weeks—absolutely all of the bacterial counts were not enough to measure.”

And Monson is right to be concerned about pathogens, says Brian Holmes, a professor of biological systems engineering and an extension specialist with the University of Wisconsin in Madison. “When you leave manure in piles, the bacteria are going to consume most of the oxygen, and it will shift over to anaerobic, and that’s not particularly destructive to the pathogenic organisms,” Holmes says. “Even with straight organic bedding, it doesn’t take too much manure contamination to have a high level of pathogens present.”

With colder winter temperatures, Monson says they made the pile larger to hold in more heat and will probably keep the material in the pile longer to ensure it’s cured thoroughly. He also continues to collect samples for pathogen testing.

As part of an “aggressive bedding” philosophy, Monson has furnished the freestall barns with cow mattresses. Until last summer, Monson put two to four inches of sawdust on top of the mattresses for added cow comfort.

In the barn housing the late lactation cows, he slowly began substituting three to six inches of the recycled solids for the sawdust.

“The cows on the manure composted solids tend to be cleaner,” Monson says. “And after two months of doing four pens in one of our barns, the somatic cell counts in three out of the four pens were lower. I relate it to the fact that the cows are cleaner.

The dairy added an IFRS 36 manure separator (above and in action at right) from Accent Manufacturing to remove the solids and accompanying odors from the flush water, improve cow herd health and possibly create another revenue source. The dairy added an IFRS 36 manure separator (above and in action at right) from Accent Manufacturing to remove the solids and accompanying odors from the flush water, improve cow herd health and possibly create another revenue source. |

“Cows just love it—they just love to lay on it. My biggest concern is it’s different from what people are bringing out of digesters. That is why I tried to take this in very slow, measured steps. So far, it appears that it works.”

With one barn converted, Monson plans to move to the other, housing the early lactation high-production cows. Factoring in labor and fuel, Monson figures it will cost him $25,000 to $30,000 annually to recycle the solids into bedding material. Sawdust, on the other hand, costs $90,000 to $100,000 annually. If down the line Monson believes sand is a better bedding material than the recycled solids, his freestall barns have been designed to allow for the change.

Partners George and Kara Kasbergen use sand at their 3,000-cow Illinois dairy in conjunction with a water recycling system. Water flushes manure and sand into settling lanes in the barn, where the sand settles out and is collected for reuse. The manure slurry flows into a treatment system.

“The system was first adopted in California,” Monson says. “Now we have dairies in the Midwest that are trying to adopt that. What we wanted to do was retrofit our existing system. If we still feel that for the health and productivity of the cows that sand is better for our management system, this system could handle it. Right now, I don’t anticipate switching.”

With the first two steps of his retrofit plan well under way, Monson says he can begin to look for outside outlets for any surplus solids. “I am very convinced that the first step has been accomplished,” Monson says. “We have cleaner water with many less odor issues. We are in the process of step two. And with step

three, if there’s material we will not be able to use, we might work with other people who are interested in this type of product.”